How death gives life

Published 29/11/2023

It’s time to shine a spotlight on the crucial role that death plays in our ecosystems, argues Rewilding Manager Sara King. She’s back from a field trip to the Netherlands where carcasses and carrion are supporting the recovery of birds, boar and more.

“Death gives life” is the literal translation of the wonderfully simple name chosen by Ark Rewilding Netherlands for their research project on the role carrion plays in ecosystems. I had the most fascinating visit to the Netherlands this month to understand how we can learn from their ‘Dood doet leven’ programme that’s pioneering new approaches to this at rewilding sites.

Here in Britain it’s rare to see carcasses in the landscape, as regulations around disease control mean that ‘fallen stock’ must be removed from land – including land in rewilding projects. As wild animals and even roadkill are quickly tidied away, we as a nation have lost our connection with this essential natural process of death. We’re missing a crucial part of our ecosystems; one which provides food, shelter and even an important moment of engagement for both animals and humans. This is a key part of rewilding that we cannot continue to ignore. Here’s why.

From food to insulation

Carcasses and carrion provide food and nutrients for a wide range of species, from wild boar to raptors and vultures. Wild boar will often consume a carcass within one night. Even predators such as wolves and lynx, who leave carcasses after a kill, will also scavenge on carrion (i.e. the decaying flesh of an animal) when food is scarce.

Alongside sustaining the creatures that feed directly on carrion, carcasses also support thousands of insects, including maggots and beetles, which in turn support a number of notable birds. Nightjars and skylarks have been recorded foraging on larvae from a carcass – an important food source during the winter months and during breeding season.

I was amazed to learn that many birds can detect carcasses from far away. Radio-tagged ravens have been recorded flying directly to a carcass, even though they’d not visited the area before.

What’s more, birds will visit carcasses to take fur for lining their nests. Studies have shown that the extra layer of warmth and protection from weather provided by this insulation improves the rate of success for chick rearing.

The bones of an animal also provide important minerals to many species – horses, cattle and even butterflies have been seen to access these areas to gain precious minerals. Magnificent purple emperor butterflies have been spotted on carcasses in the Netherlands.

Death’s ‘clean up team’

All these creatures effectively add up to a really efficient post-death ‘clean up team’. By helping themselves to flesh, bones, fur and more, they’re cycling nutrients from the carcass back into the soil. This natural process not only improves the health of the ecosystem, but actually reduces the risk of disease.

The spread of disease from the dead to the living has been widely misunderstood in the past – and we are only now coming to see, for example, that leaving deadwood in forests doesn’t in fact increase the risk of disease to live trees, as was widely believed in the 1970s. Deadwood is now recognised as an important part of our ecosystems.

I believe we’re slowly starting to see that shift in the perception of carcasses in the landscape too. Recent research undertaken as part of Ark Rewilding Netherlands’ Circle of Life project has shown that carcasses are of limited risk in spreading disease. Indeed, on one site I visited in the Netherlands as part of the symposium, Slikken van de Heen, a roe deer carcass was lying within metres of a herd of grazing red rebelcattle without causing an issue.

Did you know that herd animals mourn?

Dead or injured animals are often quickly removed from the landscape, but I learnt on my trip that mourning a death is a common behaviour for many herd species. Cattle, horses and bison have all been observed staying with dead members of the herd for a long time before they move on. Should we restore this opportunity for animals to mourn their dead?

Visitors are fascinated by carcasses

What really struck me on our visits to the two rewilding sites was that carcasses were also located close to the public footpaths that ran through them. At Slikken van de Heen a bison had died naturally within metres of a wildlife hide; at Oranjezon carcasses from roadkill had been placed close to footpaths, just out of sight. This meant that those visitors who wanted the opportunity to engage with and see the carcass decompose could, with the aid of interpretation boards that explain the process.

The project teams on the sites have also taken several school children to visit the carcasses as part of their engagement activities, giving them a chance to learn about food chains, ecosystems and more. The feedback was that the kids found it absolutely fascinating. I have to admit, there is a special feeling when standing next to the bones of great animals like bison – it’s absolutely mesmerising.

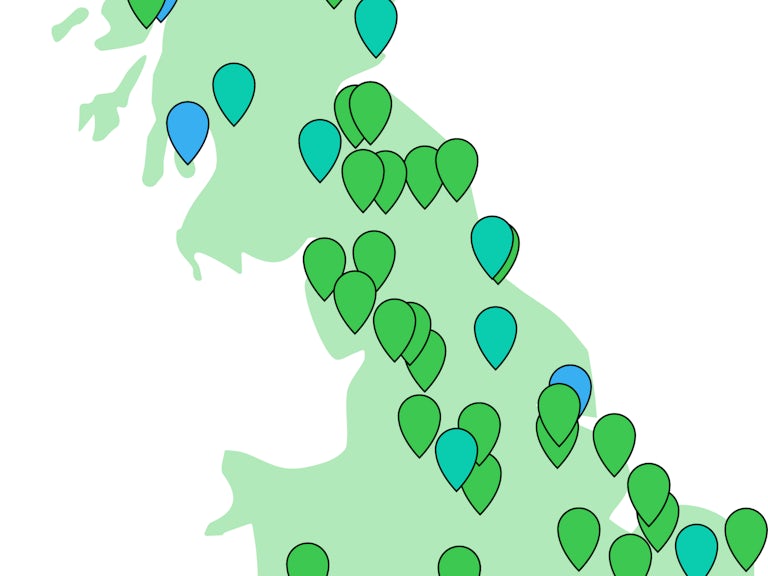

I’ve come away from the trip feeling hopeful that we can achieve change here in Britain. In the Netherlands practitioners have been dealing with the same legal restrictions, but they’ve found a way to introduce sensible exemptions for rewilding sites. The journey won’t be straightforward, but for a start we will be feeding this newfound knowledge into the fast-growing Rewilding Network and into the Large Herbivore Working Group, a collaboration of organisations looking to remove barriers to wilder herbivores in Britain.

We must learn from examples across mainland Europe – with their scientific evidence and their valuable experiences – so that rewilding projects in Britain can play their full role in restoring missing natural processes to the countryside.

Image credit: Horse on track © Martin Wright

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network