Reforestation in Norway: showing what’s possible in Scotland and beyond

Scotland and Norway suffered large-scale deforestation over centuries but over the last 100 years the trees have been returning to Norway. It could be happening in Scotland too.

Published 20/01/2016

Some people think that the reason there are no trees growing across great swathes of Scotland is that they can’t grow in these places – it’s too wet, it’s too windy, the soil is too thin. But they’re wrong. Look at the landscape in Scotland today and you’ll see a diverse mix of trees hanging on the edges of streams and gullies and rock faces. They’ve survived for centuries in extreme fringe locations where grazing mouths can’t reach them.

The forests of Scotland could return – if deer numbers were reduced to a level the land can support, if land wasn’t burned to favour shooting birds, and if livestock was managed alongside woodland as it is in many other countries.

Reforesting is part of rewilding. Rewilding is about dedicating areas of land to nature, where nature decides the outcome. We can see what that might mean for Scotland by looking across the water to southwest Norway – an area almost identical to Scotland in climate and geology.

Southwest Norway has an overall population density higher than the Scottish Highlands. However, working rural properties are much smaller than the typical holding in Scotland. They are usually owner occupied. Land use in Norway is diverse, with each property typically gaining income from a mix of activities such as agriculture, grazing, forestry, hunting and fishing sales, fuel wood production and cabin sales/rentals.

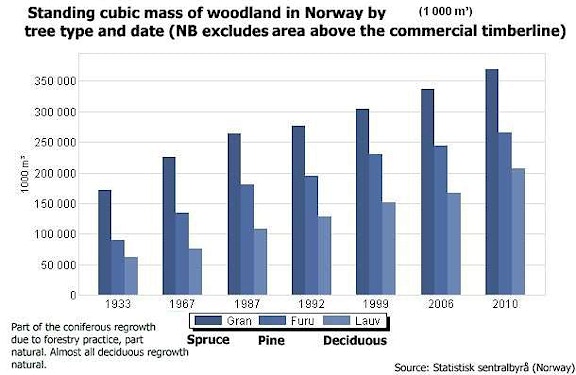

Like Scotland, Norway was once widely deforested – in coastal regions almost completely so since at least the Bronze Age. It has reforested, largely through natural regeneration, since the late 19th century, and especially since the 1950s. Research shows that this regeneration has been a result of reductions in domestic livestock grazing and associated land uses (such as muirburn).

Here’s what Norway shows is possible:

1. Bare hills can return to forest

Look at the pictures below. The top photo is of Fidjadalen in southwest Norway in 1927. The bottom photograph is Fidjadalen 2019. Like most of the southwest, the area had been almost entirely deforested. Now, even though the mountainsides are steep and rocky, the trees have returned.

-

Fidjadalen, Norway — 1927 © Photographer unknown -

Fidjadalen, Norway — 2019 © David Hetherington

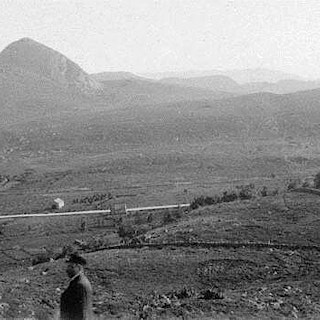

The next pictures show Oslibakken near Stavanger. The top black and white image was taken in 1911 and looks remarkably like many parts of Scotland. The bottom image shows Oslibakken in 2015, where X marks the approximate spot where the black and white photo was taken.

-

Oslibakken, Norway — 1911 © Henrik Jakob Lelstrup -

Oslibakken, Norway — 2015 © Erlend Tøssebro

2. People can co-exist with trees

And do all sorts of activities! Nearly 10 per cent of the population in Norway are registered to hunt. Red and roe deer, and grouse, are the main game species. There’s also sheep farming in Norway, with sheep typically grazing on open land and in woodland. Getting outdoors is a part of life in Norway. Kindergartens often take children on day trips to the woods. Outdoor excursions and longer overnight stays are required parts of the education curriculum. There are nearly 400,000 summerhouses and cabins in Norway – that’s one per 12 people.

3. Trees can provide economic opportunities

It’s not all about reversing the dramatic decline in biodiversity, restoring nutrients to the soil, helping wildlife thrive, soaking up C02 or helping flood prevention. Norway shows us that woodland can promote economic activity in its own right, creating jobs as well as a variety of wood based products.

4. Trees can grow on blanket bog, rocky screes and in the face of extreme wind

It’s true that trees won’t grow everywhere, but they’ll usually have a damn good try. In Norway, trees are growing naturally even on rises and hummocks in blanket bogs, hard infertile rock types, and extremely wet and windy coastal conditions.

The picture below is of Kirkehavn at the entrance to Hidrasund, an area regularly battered by westerly gales. “From Scottish experience most people wouldn’t expect that trees could grow on such an open, rocky coastal locations, annually hit by storm-force winds,” says ecological researcher Duncan Halley. “But they do”.

-

Trees growing at Kirkehavn which is regularly battered by westerley gales © Duncan Halley -

Tree growth on drier areas of blanket bog is ubiquitous in Norway © Duncan Halley

And how about this demonstration of birch and aspen colonising open scree…

5. Trees can grow high up on the hills

Anyone who has been to Europe’s mountainous regions or to wild places elsewhere should know that trees can grow high up on mountainsides. Most of Scotland’s hills are not too high for trees. However, we have lost most of the montane scrub that would exist at the highest levels (what Trees for Life calls the ‘wee trees’) and almost of all of our natural tree lines.

The picture left below shows the transition between pine and birch on the sides of a mountain in south west Norway. These natural transitions between tree zones no longer exist in Scotland. We have only one or two natural tree lines left.

The view below right is looking west south-west from the shoulder of Jarekollen in SW Norway at around 900 metres. This is roughly the height of Ben Vane, Scotland’s smallest Munro. The snowy peak in the distance, to the left of the picture, is Voilenuten at 1,343 metres (around the height of Ben Nevis).

-

Transition between pine and birch on the sides of a mountain, Norway © Duncan Halley -

View south-west from the shoulder of Jarekollen, Norway © Duncan Halley

As a contrast, this view below is from Ben Vane at 915 metres. It’s a fairly typical view of Scotland. No trees except for some commercial forestry off in the distance (definitely not natural tree lines).

So why is Scotland so different from Norway?

The problem in Scotland is not that the land is marginal or the weather too extreme. The problem is that of land management practices resulting from our very different social histories.

In SW Norway, there was large-scale voluntary migration to the USA in the late 19th and early 20th Century when the US government offered free plots of land to incomers. Many labourers on the land left to seek a new life where they could own their land. Their grazing animals left too.

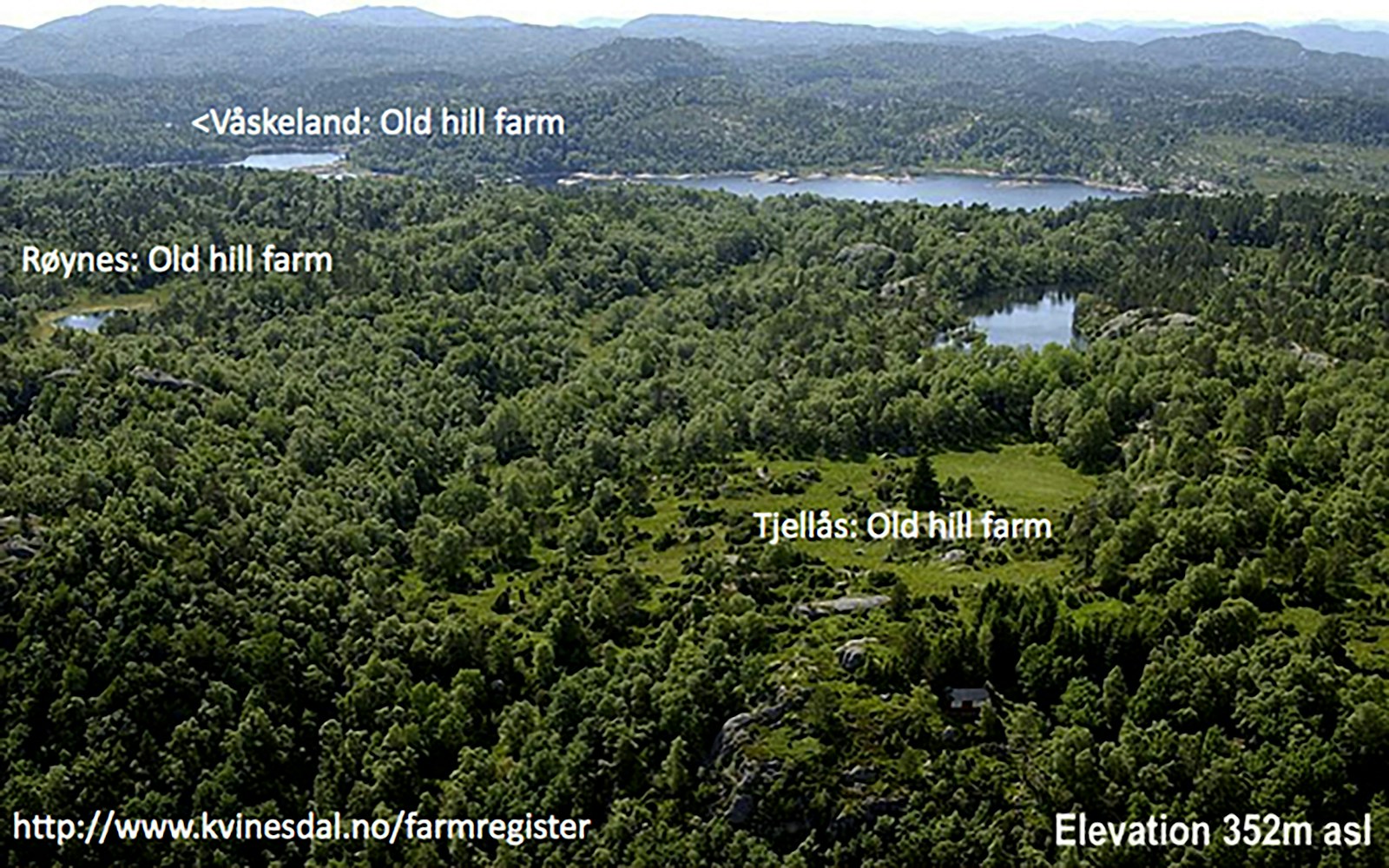

From the 1950s, social and economic changes meant many hill farms went out of permanent use as other occupations became more available. As grazing pressures reduced, reforestation started to occur. In Norway, there is still some grazing from sheep and cows, and wild grazing from moose and reindeer, but the numbers are manageable and don’t impede on the natural rate of woodland regeneration.

The picture below shows an example of the change in land use that has occurred in Norway.

In Scotland, the clearances forcibly removed many people from the Highlands in the 18th and 19th Centuries to make room for lucrative large-scale sheep farming. The cleared land was later snapped up by wealthy Victorians to establish sporting estates. These estates exterminated competing wildlife and actively encouraged a growth in deer numbers. The grouse shooting estates burned the land to favour heather growth for grouse. This has kept such land in an artificial treeless state.

A few wealthy Britons built sporting lodges in Norway in the 19th Century. They were never the dominant influence that they are in Scotland. The few lodges they built are now mostly hiker’s association cabins. There is still hunting for food and sport, which helps to keep deer numbers at a level the land can sustain. The natural regeneration of their trees is testament to that.

In Scotland, more than half of our native woodlands are in unfavourable condition (new trees are not able to grow) because of grazing, mostly by deer. Our native woodlands only cover four per cent of our landmass.

In conclusion

As in many parts of the world today land use is a product of history. Whether existing land use is the best for owners, rural communities and wider society should be questioned, especially in the face of changing attitudes to hunting wildlife for pleasure, subsidy reforms and climate change.

Rewilding can bring many new economic opportunities to rural areas and help connect land use and ownership with multiple benefits for wider society. These include mitigation of flash flooding and helping to suck up carbon emissions. Rewilding gives space to communities and nature to thrive.

About this article

Thanks to Dr. Duncan Halley for providing the factual information (and images) from Norway on which this article is based. Duncan is an ecological researcher working for the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA).

His presentation is based on studies of the south west of Norway, an area covering 33,318 square kilometres. This is comparable to the area of land covered by the Highlands, Western Isles and Argyll & Bute, 35,639 square kilometres.

Find out more about land use in Norway and Scotland on NINA’s website.

Explore our Rewilding Manifesto

Learn more

Our vision

We have big ambitions. Find out what we’ve set out to achieve through rewilding.

Our vision