Making woodlands wilder

Woodlands can be natural, planted, native, ancient and more. We explore how a rewilding approach to managing woodland might look.

13%

of Britain is woodland compared to a European average of 37%

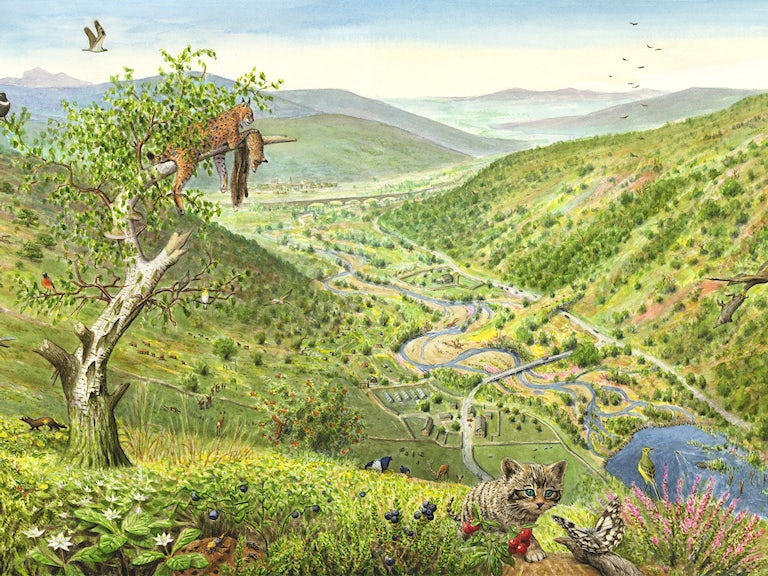

Rewilding is about restoring ecosystems to the point where nature can take care of itself, which makes woodlands in Britain one of the most challenging habitats to truly rewild. We’ve altered our woodland ecosystems dramatically; through felling, clear cutting, planting, draining, the introduction of non-native species and the loss of key species such as bison, elk, boar, beaver, wolf and lynx.

In the absence of human management these altered woodlands can become dark and uniform places, with little vegetation cover at ground level, relatively low biodiversity and too many invasive species. Many woods are struggling to survive, unable to regenerate due to over-browsing. In some places deer are fenced out to protect young trees, but the fences never come down, which means the deer never interact with the woodlands in the way they should.

Consider woodlands on a wildness spectrum, with primeval wildwood at one end, sensitively managed semi-natural woodland in the middle, and commercial non-native conifer plantations at the other. The aim of rewilding is to push woodlands towards the more natural, wilder end without being focused on any particular end points (for example, which percentage of canopy cover should be native broadleaves). Rather, nature is left to unfold in its own way.

What you do with any woodland largely depends on what you’re starting with, and what (if anything) you’d like to use the woodland for. If it’s ancient woodland in good health, you may do very little. If you have a non-native conifer plantation, the path to restoring it to more natural woodland is clearer — gradually remove the conifers and support the regeneration of native broadleaves. If you have a Plantation on an Ancient Woodland Site (PAWS), extra care will be needed.

First things first

The first thing to do is get to know your woodland. Spend time in it. Observe what’s there and what happens throughout the year. Be still, listen and look around. If you’re completely new to woodlands, and you don’t know what you have, you might need help. You could commission a survey to help you see what you’ve got and whether it sits on an ancient woodland site. The Woodland Trust can also provide excellent advice and support on woodland restoration.

Simply taking a lighter-touch approach can go a long way in wilding up woodland. Intervene only where necessary, and include more low or no-intervention zones. Helping to diversify tree ages and stages of succession is important. This can be done through thinning and planting, and taking a Continuous Cover Forestry (CCF) approach. This aims to maintain forest stands in a permanently irregular structure. Most importantly, allow natural regeneration where possible. Nature really is the best planner.

You should resolve to make your wood a no-take zone, and leave all deadwood. Natural woods are messy and full of deadwood. This should ideally be a mixture of standing and fallen trees, and be a mix of species in different stages of decay. This can be standing or fallen trees, and be a mix of species in different stages of decay. Deadwood is an essential habitat for many woodland species and is crucial for nutrient cycling. In the UK, it’s often removed for safety, tidiness, timber or other use.

You might want to lend your woods a hand by ring barking and ‘felling to waste’ a small percentage of trees, just to increase the quantity of standing and fallen deadwood. Choose these trees carefully though, and include a variety of species. Keep rare specimens and the oldest individuals, especially veteran trees.

Wild woods often have boggy and swampy areas. These areas have been drained in many woodlands to ease human access. You might consider blocking drainage features, but be aware that this could change the species composition (a concern in ancient woodland) and make your woodland less accessible. It could also affect neighbouring land users.

“Deadwood is an essential habitat for many woodland species and crucial for nutrient cycling.”

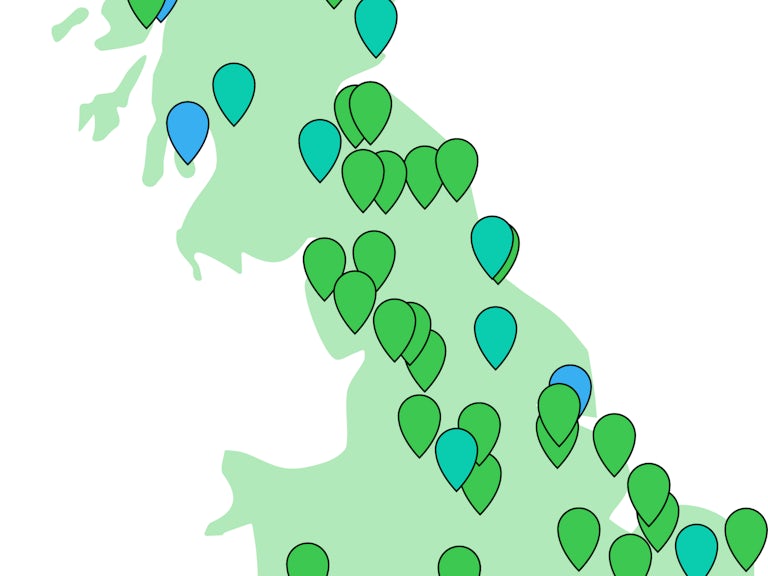

We’re boosting rewilding on the ground

A woodland scoping study at Glenlude is one of 11 projects awarded in the latest round of the Rewilding Innovation Fund. The study will help shape a plan for native woodland restoration that complements low-impact forestry.

Uncover the full list of recipients awarded since 2021 to see the diverse range of rewilding projects taking action across Britain’s land and sea.

Natural processes

A rewilding approach favours wildlife-mediated natural processes over human intervention. You may consider reintroductions of wild species or introducing domestic proxies to take on the role of the wild. For example, Tamworth pigs can be effective wild boars. Cattle can play the role of the extinct aurochs. Horses and deer add to a mixed grazing pattern, and beavers are becoming more socially acceptable in our landscapes again.

Overgrazing is common in Britain, particularly by sheep and deer. If your woodlands are in poor condition, you might need to exclude grazers and browsers, at least temporarily, to help recovery before introducing others. There are a few things to consider in this context:

- The level of browsing pressure the woodland is (or has been) under

- The size of woodland you have and whether it can support such species

- Whether you are able to adequately fence animals in – or out

- How ready you are for owning livestock – a significant and expensive commitment

Wild animal reintroductions can require significant resources and expertise, and not all of your neighbours might be on board. There may be other ways you can support reintroduction efforts or rare wildlife, such as installing habitat boxes (for pine martens or rare birds, for example) or controlling grey squirrels.

Speak to conservation bodies, wildlife trusts and other landowners to find out what’s going on in your area. Try to link up areas of woodland where you can. Connectivity is vital to flourishing wildlife. Smaller rewilding areas can achieve scale through connecting and joining up.

Allowing woodland species to disperse into surrounding fields through natural or assisted regeneration is one way of doing this. If you’re considering buying woodland or land to rewild, find out who your neighbours are. Being close to a large-scale project, similar habitats or amenable communities will all help.

Wildwood management

Rewilding British woodlands, at least those under small-scale private ownership, will look quite similar to traditional woodland management – particularly in the absence of key, often controversial, species. Traditional techniques share the rewilding ethos of looking to nature for guidance, often mimicking the natural processes and disturbance regimes of the missing animals.

For example, coppicing (the cutting back of trees to stumps on a 5- to 20-year cycle to harvest wood and stimulate regrowth) opens up areas to light and creates a diverse age-mix. It mimics the actions of bison, elk and beavers before we hunted them to extinction in Britain.

Whatever changes you make, do them slowly and with keen observation. Rewilding is a long-term thing and nature works to its own time-scale, far beyond our short human life times. Gradually nudge your woodland towards a more natural, wilder wood with patience as well as enthusiasm. Seek advice and connect up as much as you can. Help natural processes where you can. It will all contribute towards creating a more wooded, wilder, healthier Britain.

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network