Measuring and monitoring rewilding

Monitoring change can help inform your rewilding strategy, gauge progress and mark the marvellous meanderings of your journey.

Understanding what wildlife and species you have on your land, and measuring changes as you start to do things differently, is an important part of rewilding. This is an area that abounds with expertise and enthusiasm in the UK. If you’re new to it all, then you’ll probably want to enlist some help. But here’s the lowdown on what you should be thinking about and where you might look for advice and assistance.

Biodiversity

You can monitor many different species groups to show changes in biodiversity on your rewilding site. The species you choose will depend on what questions you want the data to answer, and what habitat and opportunities for wildlife are present on your site. Local wildlife groups, such as the relevant county Wildlife Trust and Local Nature Partnerships should be the first point of call for advice on existing schemes for monitoring, but we have provided some popular monitoring subjects to get started with below.

Bats use many different habitats, and can show change in habitat structure and invertebrate levels in a short space of time. You can monitor bat populations through bat walks and installing remote detectors that can record activity over a longer period of time. Your local bat group should be your first point of call, and will be able to help with data collection.

It’s important to know which species you have using your site, whether it’s beavers and boar or hedgehogs and squirrels. Camera traps can be used to record animal movements across your site, and are low cost. These can also provide interactive photos to help promote your project to others. If you have lots of camera trap photos, you can get help with identifying them using citizen science apps such as Instant Wild.

Pollinating insects are important for our ecosystems, as they fertilise plants, and are vital to many ecosystem services including food production. Monitoring pollinators can give a good indication of whether your site practices are supporting a healthy ecosystem. You can link this survey work up with the UK Pollinator Monitoring and Research Partnership (PMRP). Usually, bees and hoverflies are recorded as these provide a high proportion of pollination to crops and wildflowers. You can collect data during bee walks and transects using volunteers and mobile apps to help with identification.

Butterflies can provide information on habitat type and variation, as well as changes in local climate. They are also a great way to get people involved in your project. The Butterfly Conservation Big Butterfly Count will allow you to collect data that contributes to the national monitoring scheme, as well as collecting data on butterfly populations within your project.

Moths and their caterpillars are important food items for many other species, including amphibians, small mammals, bats and many bird species. They’re good indicators of ecosystem health, and being sensitive to change can give us clues to how our actions are affecting the ecosystem. Monitoring moths can be extremely interactive (the best way is to use moth traps to record moth populations in spring, summer and autumn). These can be purchased or home made. Mobile apps have been developed to help to identify moth species and the number of moth trapper/recorders has increased dramatically in Britain in recent years, with well over 10,000 now active.

There are many long-standing bird monitoring schemes in the UK. This means you can compare recordings on your site to national trends. They can also help you record changes in bird populations, the types and species of birds, the abundance of birds, and any changes to threatened bird species within your rewilding project.

You can monitor bird populations using existing schemes, such as the BTO breeding bird survey schemes or via local bird groups. You can also record birds using bioacoustics and expert surveyors to monitor change in specific areas of your project.

Soils

Leonardo da Vinci famously said that “we know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil underfoot”. Soil health underpins our ecosystems, and it’s vital to understand how our actions are affecting it. Unhealthy soils can result in decreased vegetation, increased surface run-off and flooding, and decreased drought tolerance. Healthy soil results in healthy vegetation, animals, wildlife, and a functioning ecosystem.

A basic way to assess your soil is to undertake a visual inspection. For example, searching for signs of erosion, and whether soil is running off into watercourses on your site. You can also take a soil sample from a number of different areas and record soil properties to monitor change over time. Properties to record include soil colour, structure, type of soil (e.g. clay or sandy), levels of compaction, organic matter and whether particles are coarse or fine. This can provide good information about the health of the soil.

For a more in-depth analysis of your soils, you can undertake soil testing. This is undertaken by a laboratory, and can provide information on organic matter content, carbon content, pH and levels of soil microfungi. These all provide information on how healthy and functioning your soils are. Carbon content information in particular, will be hugely valuable in helping to assess how your rewilding project is contributing to climate change mitigation. In addition to providing a baseline for assessing change over time, soil tests at the start of the project can provide information on whether additional restoration or intervention is needed to restore natural processes. Some laboratories link soil testing to wider soil community monitoring, which enables you to benchmark your site against others in the local area.

Earthworms are one of the key organisms in the soil, they not only help nutrient cycling and process organic matter into new soil, but also increase aeration and gaps within the soil increasing infiltration rates. The levels of earthworms in the soil can indicate the health of the soil ecosystem. They are also easy to measure - count the number of earthworms in each location when you conduct your visual assessment. You can also get community groups involved with widespread monitoring of your project.

Vegetation

Vegetation and habitats are likely to continuously change throughout your rewilding project through natural succession. A healthy ecosystem is subject to a constant cycle of vegetation change, especially where herbivores are present. Monitoring vegetation extent can provide information that can inform your on-going project, such as ensuring that the levels of herbivores are not affecting the ecosystem through overgrazing, as well as understanding the natural processes that exist on your site. Quadrant monitoring at fixed points is particularly valuable in identifying changes in plant communities over time.

Fixed point photography is an effective way to monitor site changes. It is used for many different large scale ecological projects around the world, and is easy to implement. Regular photographs are taken in the same location. These photographs are compared to show change over time, and to observe how habitat and vegetation structure has changed. You can take the photographs yourself, or you can install wooden frames to encourage visitors to take photos and send them to you for a more comprehensive record. The photos can also be used to promote engagement with the project.

A habitat survey aims to identify the habitat types on site, and map their extent. This provides an assessment over time that can show how rewilding areas are changing, and the natural processes that are in place. A qualified ecologist can undertake the survey, or drones and aerial photographs can be used.

Water

Most rewilding projects will help to slow the flow of water off the land and so this will be one of the most important aspects of monitoring for rewilders to consider. Ideally this would involve installation of flow gauging in watercourses which drain from rewilding areas, but of course this can be expensive. As with measurement of other ecosystem services such as soil and water quality, it is therefore well worth contacting the relevant departments of local universities and colleges to see if they would like to instal monitoring equipment in new locations to provide study sites for students and research projects. As with all of these monitoring aspects, it is important to start monitoring before any rewilding interventions have commenced in order to establish the baseline against which to measure change.

You can undertake visual assessments of water quality on your project by recording the amount of algae, silt and material in the water, and any obvious pollution. You can also conduct aquatic invertebrate sampling to record water quality changes. Many aquatic invertebrates are indicators of good water quality. The abundance of invertebrates also gives an indication of overall ecosystem health. There may be a local recording scheme, local group, or ecologist who can assist with this type of survey and as with water quantity measuring, it is well worth contacting local universities and colleges.

People

People, communities and livelihoods are key to thriving rewilding projects. Monitoring people and enterprises is just as important to understand that impact of your project, as well as change over time.

Many rewilding projects have public access, recreational activities and tourism included in their strategy. All of these help people reconnect with nature, improve wellbeing, and understand your project. You can monitor how people are interacting using social media; are visitors coming for the view, to forage berries, to see the wildlife, or to camp? You can review social media uploads to create heatmaps of activity across your site, or encourage visitors to post photos and their views to social media using a hashtag. This will provide an extra perspective of how visitor interactions change over time, and the impact that you are having.

Rewilding projects can support a range of enterprises and businesses, within the project and within the local community. Monitoring and recording the impact of this is really important for informing future business diversification and new opportunities in the local community. In addition to recording your own enterprises, speak to your local community to understand the impact your project is having on other businesses over time. As with some of the ecosystem service benefits mentioned above, the socio-economic aspects of rewilding are a growing area of interest for academic studies, so again it is well worth contacting local universities and colleges to see if they would be interested in conducting more formal assessments of these potential benefits.

It’s likely that you will need to provide more energy and effort into your rewilding project at the start. For example, by implementing restoration interventions, management to restore natural processes, and investment in alternative herbivores and infrastructure (such as camping facilities). Human inputs should reduce over time, so monitoring your inputs is important to inform your ongoing strategy. If you are still inputting high levels of management on your site after many years, then you will probably need to review your strategy to ensure it’s working with natural processes and not against them.

Other

Experiment with tools and apps that can help you measure and monitor, and sign up for existing recording schemes. For example:

ZSL Instant Wild

ZSL’s Instant Wild app empowers you to take part in vital conservation work, bringing you live images and videos from locations all around the world

The Big Butterfly Count

UK-wide survey aimed at helping assess the health of our environment simply by counting the amount and type of butterflies

National Moth Recording Scheme

You can use the data collected to contribute to national datasets

Breeding Bird Survey

The BTO Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is the main scheme for monitoring the population changes of the UK’s common and widespread breeding birds

Join the Rewilding Network

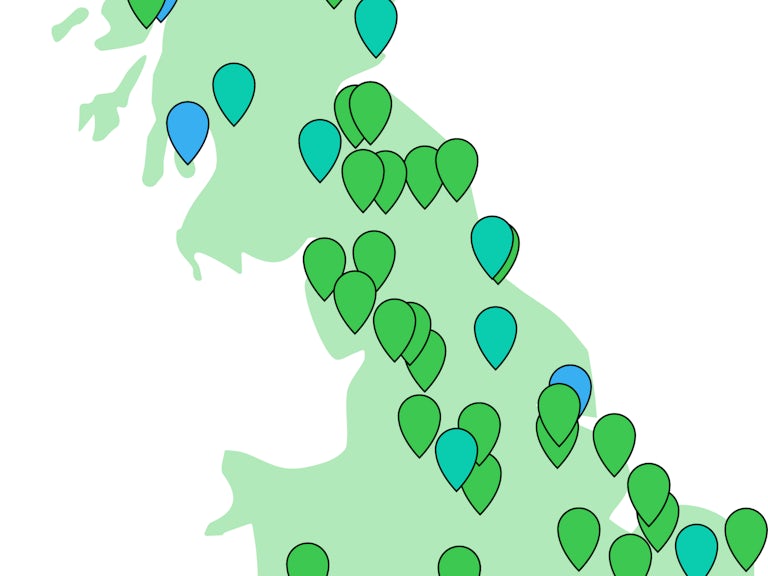

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network