Webinar: Natural tree regeneration in action

Three experts explain what makes a forest, how they grow and what you can do to encourage woodlands to grow and expand.

This webinar was held for members of the Rewilding Network on Tuesday 23 February 2021.

Natural tree regeneration is a complex subject that can’t be fully explored in one webinar (please read more on our Natural Regeneration page and see Rewilding the land for more). Nevertheless, our speakers gave a great introduction to the topic and lots of practical examples of native woodland restoration.

Speakers

Fraser Bradbury, forest and environmental manager, Westacre Estate

Fraser manages the regeneration and rewilding of the Westacre Estate in Norfolk. The estate started rewilding its lowland farmland in 2020 to restore biodiversity and create new nature-based enterprises.

Lee Schofield, site manager, RSPB Haweswater

Lee oversees the management of two upland farms with extensive common grazing rights, all within the catchment of Haweswater reservoir. Working in partnership with United Utilities, Haweswater aims to deliver a range of public benefits including biodiversity gains, improvements to raw water quality and carbon stewardship, while maintaining a viable farming enterprise.

Adrian Kershaw, community engagement, Borders Forest Trust

Adrian focuses on community engagement for BFT’s rewilding project in the Scottish Borders: Reviving the Wild Heart of Scotland. This large-scale ecological restoration project focuses on restoring trees to the valleys.

Natural regeneration at Westacre

Fraser Bradbury from Westacre estate in Norfolk packed in a wealth of information on his experiences of natural regeneration.

It’s important to think in terms of forests and woodlands when we think about natural regeneration and rewilding on a larger scale, said Fraser.

“Forest conditions create forests”

Fraser Bradbury

Westacre Estate

Forests are more than just a collection of trees. Defined as having at least 20% tree cover, they are more open than we think, an ever-changing mixture of rich habitat for wildlife and carbon sequestration.

Intricate root systems and networks of mycorrhizal fungi lie beneath natural forests and woodlands. These connect trees with each other and with the fungi and plants also present.

“Forest conditions create forests”, said Fraser. In other words, it’s difficult to bring back forests and woodlands from nothing, on ground where seed sources have been lost and soils destroyed over centuries.

Woodlands have their own microclimate, which includes soils, mycorrhizal fungi, vegetation, nutrients, shade regimes, aspect and light levels. Site conditions have a huge impact on natural regeneration.

Understand what you have

Knowing the tree species suitable for your local area, and how they are adapted to their environment, is crucial to understanding how a forest naturally develops. Reviewing your flowering and fruiting trees in spring and summer can provide an overview of likely regeneration potential and seed sources.

It’s worth also having a look around your wider local area to see which species do well. That will give you an indication of what is likely to grow well on your land. Disease and weather events can have an impact on the available seed source. For example, a late hard frost may reduce the availability of some fruits for a growing season.

Don’t forget that deadwood and fallen trees can create great conditions for natural regeneration.

Lend a hand

We sometimes need to intervene to give regeneration a helping hand. This can include protective measures, such as fencing (to exclude herbivores), direct seeding, planting (ground cover as well as trees), scarification of the land to encourage regrowth, or tree guards.

If you’re starting with bare land or a cleared area, the growth of rank weed, thatch and very dense bramble can prevent natural regeneration just as much as high levels of browsing and grazing can.

Open glades are needed to allow light to reach seedlings. This can be created through animal disturbance (at low densities), tree death or from interventions. Dense bracken may be broken up to encourage light through for seedlings to appear.

Other lessons learned

Bramble trouble

Thorny scrub doesn’t always help the establishment phase. When it’s dense it can stop seeds and light from reaching the ground. Bramble can also get away and pull down the trees that are trying to grow. It’s best to monitor this and mimic natural disturbance by herbivores where needed.

Weeds suppress

Weeds and damaging agents, such as nettles, can suppress natural regeneration. In one example, hand weeding was undertaken for three years. Despite this, nettles have swamped the area and only one cherry sapling made it. A springtime cultivator was used to open up the area and prepare the soil for regeneration.

Leaf predators

In addition to browsers and grazers, some leaf predators can affect natural regeneration, especially when present in large areas.

Animal impacts

Deer, voles and other animals can have a massive impact. Voles in particular go through boom and bust years, and can kill an entire stock of regeneration when in high numbers. Deer can do the same (see top tip about sheep wool below). There isn’t a practical solution to vole and small mammal damage. Quantity and quality of available foodstuffs will reduce impact, and small mammal guards can protect above ground growth. In areas with little available food and a large population, root damage is likely. Just monitor and be patient.

“Sheep’s wool can be put on saplings to reduce browsing from deer”

Fraser Bradbury

Westacre Estate

Sheep’s wool deters deer

Sheep wool can be put on saplings to reduce browsing from deer — a top tip from Fraser.

Dense vegetation

Once light levels have been lost and rank vegetation becomes established, even boar and bison will make little difference. Human intervention is likely to be needed in such a situation.

Deadwood demands

Retention of deadwood is important, and should be present in different stages of decay and be a diversity of species. Pollarding can also assist in the creation of internal deadwood within a woodland.

Assisting natural regeneration in the uplands: RSPB Haweswater

Lee Schofield from RSPB Haweswater spoke about natural regeneration in an uplands setting.

Upland habitats are often slow to regenerate due to their depleted soils, exposed and steep banks, poor seed sources and historical intensive grazing, said Lee. Understanding local geography, along with natural and cultural history, is important before any rewilding project is undertaken.

Bracken in the landscape indicates woodland soils, and the potential location for historical woodland habitats. Place names can also give an indication of historical habitat. In addition to identifying the features on your site, do a desk study to understand what your site may have lost, and how it sits within the wider landscape.

Once restored, woodlands will stabilise and enhance soils, store carbon and improve water quality. Natural regeneration is encouraged at RSPB Haweswater but many areas of the project are unlikely to recover without assistance due to a lack of seed source, nutrient-starved soils, and the impact of wild grazers.

The project aims to balance hill farming and ecological restoration, and is a landscape laboratory for testing new approaches.

“Bracken in the landscape indicates woodland soils, and the potential location for historical woodland habitats.”

Lee Schofield

RSPB Haweswater

Right habitat in the right place

Local provenance for tree planting is important. RSPB Haweswater has developed a local tree nursery where stock is grown from seeds and cuttings collected across the reserve. This can support a strong mix of local genetics as well as naturally selecting species that are adapted to local conditions.

Woodlands are planted in a naturalistic way using multiple approaches: cages, tubes, clusters, bare planting, and planting in bracken. This involves volunteers, and can be a great way to engage local communities and ensure community support for a project.

Once established, these planted trees will provide a natural seed source for future woodland regeneration.

Other lessons learned:

Avoid peat

Avoid planting on peat soils – peat locks in high levels of carbon and should not be disturbed as it is a valuable habitat in its own right.

Give assistance

In an upland habitat with little to no seed source, some intervention is needed. If you sit back and wait for natural regeneration to happen, you are likely to be waiting 100 years. We can’t wait this long to tackle the climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis.

Mimic nature

Be as natural as possible when planting, and consider clusters of trees to act as seed sources for future natural regeneration. You are seeking to supplement nature here, not replace it with traditional tree planting.

Creating a woodland in sheep grazed landscape: Borders Forest Trust

Adrian Kershaw from Borders Forest Trust spoke about the role of planting and volunteers to kickstart rewilding.

The Borders Forest Trust manages an inspirational rewilding project in Scotland, which includes the Carrifran Valley. Centuries of sheep grazing had reduced the upland habitat here to ‘ecological deserts’. Natural regeneration was extremely limited and restricted to isolated crags. It would have taken hundreds of years for natural regeneration to reach the valley.

“You don’t need traditional tree planting events to engage your local community. All aspects of woodland restoration can attract interest.”

Adrian Kershaw

Borders Forest Trust

Due to a lack of seed source and suitable conditions, tree planting was required across Borders Forest Trust’s three project areas in the Scottish Borders. A total of 2 million trees have been planted to date, 10% of which were planted by volunteers and the rest by contractors. This is an incredible feat given the remote nature of the project, where a two hour walk up steep slopes is regularly needed to get to the planting area.

Involving volunteers

Co-ordination was a major part of the project. Volunteers need more input and organisation than contractors but the engagement, education and wellbeing aspects of getting people involved is invaluable.

Adrian pointed out that you don’t need traditional tree planting events to engage your local community. All aspects of woodland restoration can attract interest from all sorts of people. Volunteers have also helped with bracken bashing, tree guard removal, infrastructure maintenance and monitoring. They’ve come from a range of backgrounds and included corporate volunteer days.

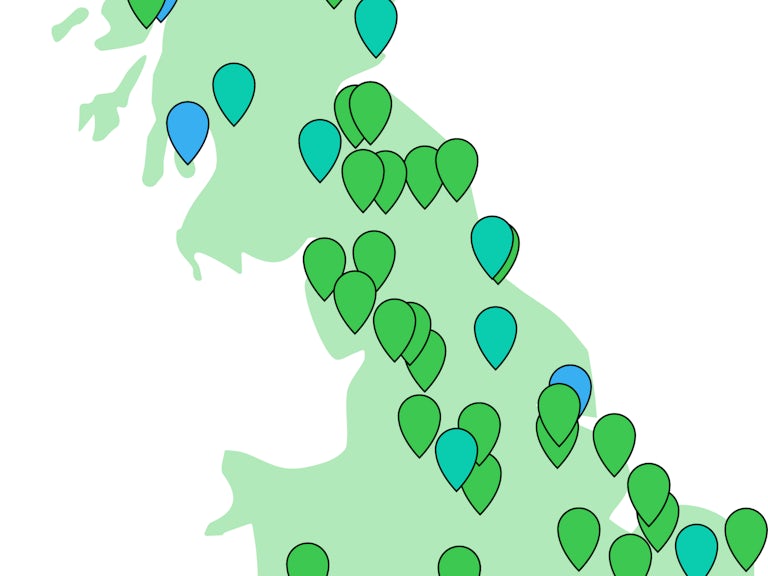

Future events

The Rewilding Network aims to facilitate knowledge exchange and experiences to catalyse practical rewilding across Britain. We host a range of events and webinars, like this one, focused on key topics as well as highlighting experiences from Network projects.

To gain access to future events, check if you’re eligible to become a member of The Rewilding Network. Membership is free.

Further reading

- Rewilding Britain: Reforesting Britain Report

- Rewilding Britain: Natural regeneration campaign

- Woodland Trust: Ancient woodland restoration

- Woodland Trust: Wood wise magazine

- Forest Research: links to research they’ve undertaken on natural regeneration

- Cumbria woodlands: Ground preparation for woodland creation course

- Rewilding Network: How do we engage communities in the absence of tree planting?

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network