Rewilding boosts jobs and volunteering opportunities, study shows

Jobs up by 47% as new “myth-busting” evidence emerges from Rewilding Britain

Rewilding marginal land can significantly boost job numbers and volunteering opportunities while increasing action to restore nature and tackle climate breakdown, new research by Rewilding Britain shows.

An analysis of over 20 sites across England covering over 75,000 rewilding acres between them has revealed a 47% increase in full-time equivalent jobs and a nine-fold increase in volunteering opportunities.

The data also shows that food production can continue on marginal land that is rewilding, with all of the sites continuing to generate income from food production, livestock and other enterprises – puncturing myths by demonstrating that rewilding in Britain is not about land abandonment or ceasing food production.

Rewilding Britain has analysed data from the 23 sites as part of its role catalysing practical rewilding through support to landowners. Many are part of the charity’s new Rewilding Network , which is bringing together landowners, farmers, land managers, community groups and local authorities from across Britain.

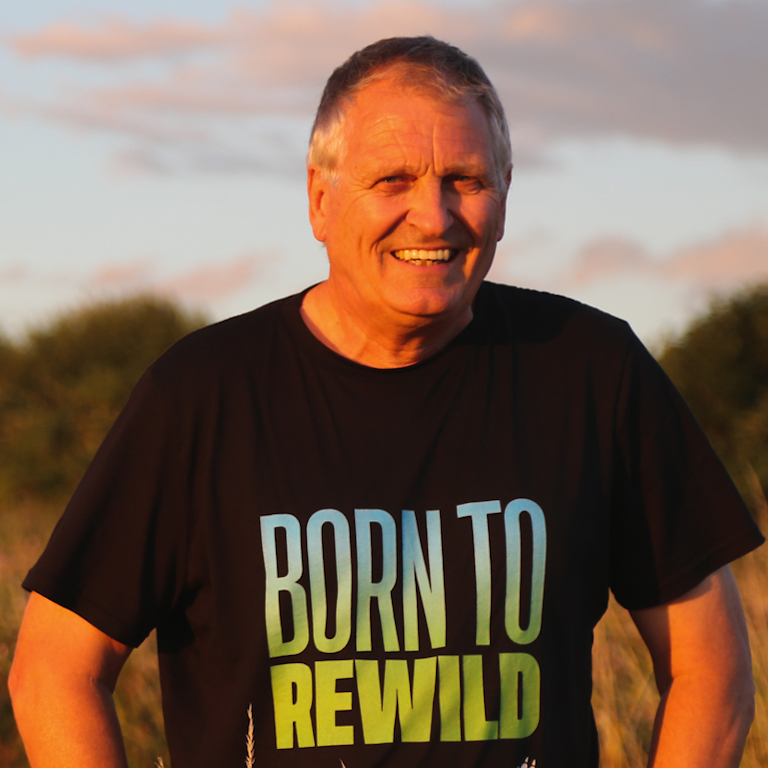

“Our findings on green jobs should be music to the Government’s ears. They spotlight rewilding’s potential for creating economic and other opportunities for people – while restoring nature and tackling climate breakdown,” said Rewilding Britain’s Director, Professor Alastair Driver, who carried out the data-gathering and analysis.

“Many of us knew that real-world rewilding projects produce food and create new job and volunteering opportunities alongside offering major biodiversity, flood risk, water quality, health and carbon sequestration benefits – but even we under-estimated the extent to which they do so.”

A variety of different-sized farms, estates and sites owned or managed by private landowners, charities and public bodies was studied. They include Upcott Grange Farm in Devon, Pirbright Ministry of Defence Ranges in Surrey, RSPB sites at Haweswater and Geltsdale in Cumbria, WWT Steart Marshes in Somerset, and Norfolk’s Wild Ken Hill estate.

The sites cover a combined total of 122,547 acres, of which 75,261 acres are rewilding – mostly on poorly productive or non-agricultural land, showing how rewilding can boost opportunities on marginal land while co-existing alongside farming for food on more productive land.

Jobs data was available for 22 of the 23 sites. Across these areas combined, full-time equivalent jobs increased by 47% – from 151 before rewilding began to 222 afterwards, over an average of 10 years. The variety of jobs involved also increased significantly, with many of the new jobs focused on nature-based tourism, monitoring, restoration activities, informal recreation, livestock management and education.

There was a remarkable nine-fold increase in volunteering opportunities, with associated benefits for people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing. On the 19 sites for which pre-rewilding data is available,the combined number of volunteers has soared from 50 to 428.

“These are really positive findings. This volunteer engagement boom brings with it physical health benefits from being in a nature-rich environment, the mental wellbeing and feel-good factor from being involved in such exciting and worthwhile projects, and opportunities to learn new skills,” said Alastair Driver.

All of the sites still support grazing animals. Livestock data, available for 15 of sites, shows livestock 54% lower than previously, solely due to reductions in sheep numbers – but with numbers of cattle, pigs and ponies all increasing slightly.

“Natural grazing is an important part of healthy ecosystems – so as part of our practical support for farmers,we encourage appropriate replacement of native but missing wild populations of elk, wild boar and extinct cattle called aurochs with their closest equivalents. Small numbers of widely roaming rare breed cattle, ponies and pigs can closely replicate the natural grazing impacts of formerly native species,” said Alastair Driver.

There have been species reintroductions on 10 of the sites, with further introductions planned on most of those areas and on another six sites – the most numerous being beaver, white stork and water vole.

Alastair Driver said: “We will continue to add new data as it becomes available and publicise the results as they emerge, but our findings already are an impressive source of optimism – and illustrate why rewilding should be mainstreamed as an option for landowners in government policies.

“We‘re grateful to all the projects which shared the data and information with us. The results are a positive reminder that people are at the heart of rewilding – to make it happen and to benefit from it.

”Rewilding Britain is calling for nature restoration across 30% of Britain’s land and sea by 2030, with 5% of this being core rewilding areas of native forest, peat bogs, moorlands, heaths, grasslands, wetlands, saltmarshes, kelp beds, seagrass and living reefs, and with no loss of productive farmland. Alongside this, the charity is calling for Government financial incentives to support more nature-friendly farming.

Although Britain should be teeming with wildlife, populations of species – from songbirds to insects to plankton – are collapsing, with some 56% in decline and 15% threatened with extinction.

Rewilding Britain wants rewilding – the large-scale restoration of nature to the point it can take care of itself –to flourish to reconnect people with the natural world, sustain communities, and tackle the extinction and climate crises. See rewildingbritain.org.uk

“This volunteer engagement boom brings with it physical health benefits from being in a nature-rich environment, the mental wellbeing and feel-good factor from being involved in such exciting and worthwhile projects, and opportunities to learn new skills”

Alastair Driver

Director, Rewilding Britain

English rewilding sites – summary of key findings

This information was collected through lengthy interviews conducted by Alastair Driver with each of the individual landowners or land managers of the 23 sites, based on a standard set of questions. Professor Driver carried out all the collation and analysis of the data.

1. Rewilding Britain has collated and analysed a wide range of data for 122,547 acres of land across 23 sites in England of which 75,261 acres (61%) are rewilding .

2. We have livestock data for 91,931 acres of land across 15 sites of which 46,223 acres (52%) are rewilding.

3. Livestock Units (based on Defra standards) after starting rewilding are 54% of those pre-rewilding.

4. The entire reduction of livestock units is accounted for by sheep numbers, which are down from 22,410 to 1,420 (6% of pre-rewilding figs).

5. Numbers of cattle, pigs and ponies all increased overall as a result of rewilding.

6. 56% of the rewilding areas across the 23 sites are in designated protected areas, i.e. Sites of Special Scientific Interest or Scheduled Ancient Monuments.

7. Some form of conservation management still takes place on 13 of the 23 sites covering approximately 3% of the rewilding areas.

8. Many different interventions have been applied or are being planned by the 23 rewilding projects to help kick-start the restoration of natural processes. The most popular interventions are: allowance of natural regeneration (all 23 sites), introduction of small numbers of other grazing animals (21), significant reduction or removal of sheep grazing (15), removal of internal fencing (14), wetland creation/restoration (13) and tree planting (10).

9. Species reintroductions have been carried out on 10 of the 22 sites and other introductions are planned on most of those, plus another 6 sites.

10. Reintroductions of 26 species (or in the case of herbaceous plants – species groups) have been carried out, or are being planned on those 16 sites.

11. The most numerous reintroductions done or planned are: beaver (11 sites), white stork (4), water vole (3).

12. We have jobs data for 22 sites, and across those sites the full-time equivalent jobs increased from 151 to 222 as a result of rewilding (47% increase).

13. The diversity of job types increased significantly as a result of rewilding.

14. We have volunteer data for 19 sites and across those sites the number of volunteers increased from 50 to 428 as a result of rewilding (a nearly nine-fold increase).

15. 14 sites reported known positive impacts on local businesses and communities and 5 of those sites also reported known negative impacts. Impacts were either not known or not yet evident for the other 9 sites.

16. 21 sites were aware of neighbouring landowner attitudes to rewilding. All 21 have at least one supportive neighbouring landowner, 13 of them also have neighbours who are sceptical and 5 have neighbours who are opposed to rewilding.

17. Some form of monitoring is taking place on all 23 sites. The main focus of monitoring is biodiversity (21 sites), soils (7), water quality (7), carbon (6), hydrology (5), socio-economics (3) and erosion/deposition (1).

18. 3 sites described engagement with Rewilding Britain as having made all the difference to their commitment to rewilding, 6 sites said it had certainly helped, 13 sites started rewilding before Rewilding Britain existed, but they all said that having our ongoing support and advice was welcome. One site (still confidential) said that the use of the rewilding word had made things slightly more difficult for them.

19. 8 of the 21 sites are Open Access land and 6 are in National Parks.