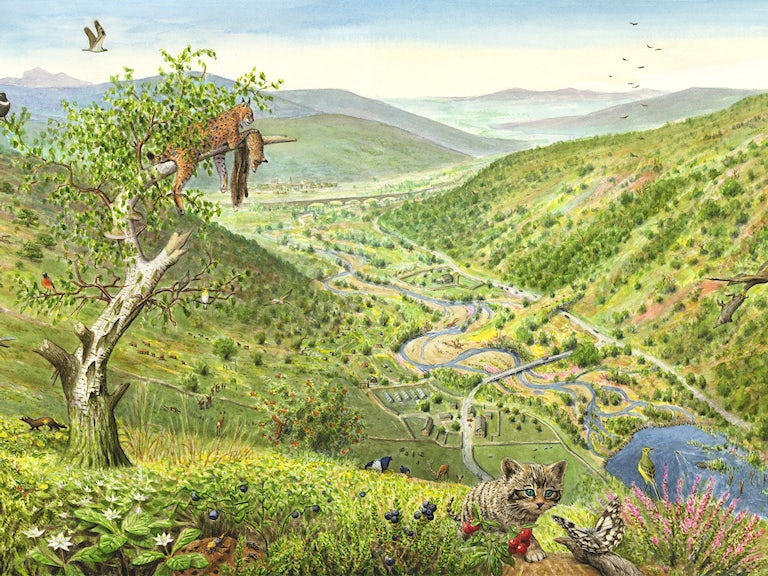

Restoring cultural identity through native breeds

Rewilding can offer an opportunity to restore local identity to our landscapes by restoring native breeds of livestock.

One thread of criticism towards rewilding is that it will result in the loss of cultural landscapes. This could be in the form of removing people from the landscape (land abandonment), changing sheep grazed cultural landscapes (such as those seen in the Lake District, often associated with Beatrix Potter and many other writers), or erasing a local area’s identity.

The truth is a lot more shades of grey than black and white. Rewilding is about restoring natural processes, and many traditional approaches to farming and land use worked closely with natural processes. They might not have been rewilding but they could be called nature friendly. Over the last 70-odd years, where agriculture has intensified, and chemicals have replaced natural ways, nature has been lost.

Sometimes rewilding can offer an opportunity to restore local identity to our landscapes, in particular through restoring native breeds of livestock. Native breeds are generally better suited to local environments and can restore a diversity to our landscapes that’s been missing for decades.

The Rare Breeds Survival Trust has a mission to protect the diversity of our native breeds. They save genetics in a UK National Gene Bank and promote the breeding and registration of rare and native breeds. Native breeds contribute to rural economies, and are part of our national identity and heritage.

They also represent a unique piece of the earth’s biodiversity – a term mostly associated with wildlife, but also relevant to native breeds of livestock. Studies have shown that native breeds can have some genetic resistance to animal diseases, and the use of them could improve the resilience of our rural areas.

We know that herbivores are a vital part of many natural processes, and in many cases removing them entirely can reduce the diversity of habitats. The first stage of many rewilding projects is to look at restoring a mix of herbivores to the landscape, including cattle, horses and pigs.

Pioneering projects provide examples of which breeds could be suited to a rewilded landscape, but it’s important to also look at historical native breeds to see what might be more suited to a project’s situation and environment.

Read more about the role of grazers and browsers

Snapshot of some native breeds around Britain

Cattle

Aurochs are extinct, but we have some ancient native breeds that are adapted to local conditions and can act as proxies on rewilding projects. The UK has 34 native cattle breeds, of which 14 are considered rare. The White Park Cattle is one of the most ancient breeds of cattle in Britain. Herds were mentioned in Wales in the ninth century, and they were brought into Britain over the Dogger Bank land bridge. Highland cattle are immediately associated with Scotland and support its cultural landscape, but they are also well adapted to the harsh conditions found in the Scottish highlands. English longhorn cattle are now very much associated with southern lowland England, thanks to their presence on the Knepp Estate!

Horses

The UK has 14 native horse and pony breeds, of which 12 are considered rare. I wasn’t aware that there were so many! Although they are stunning, Exmoor ponies are not the only breed suitable for rewilding projects. We have native Welsh ponies, Dartmoor ponies, fell ponies, and even highland ponies that are adapted to local conditions. Many of these ponies are hardy, and used to conditions including wetland areas. We don’t necessarily need to import Konik ponies for wetland areas.

Pigs

The UK has 11 native pig breeds, all of them considered rare and at risk of extinction. Tamworth pigs are a favourite breed for rewilding projects where wild boar are not present. I have to admit, I have a soft spot of Tamworth pigs, and love seeing them rootling around the Knepp landscape. But they aren’t the only breed to consider. Iron age pigs have also been used on some projects. These are a hybrid between wild boar and domestic pigs. There may also be other old breeds of pig that should be considered, especially where they are hardy and can cope with outdoor conditions.

A return of our cultural landscapes?

One of the things that excites me about rewilding projects is the opportunity to restore diversity and variation to our landscapes (and seascapes), but also to regain local identities. How amazing to be able to travel through a landscape and to know where one is on the basis of the habitats seen out the window, and the breeds of cattle and horses freely grazing those habitats.

Understanding local native breeds is an important stage of developing a rewilding strategy. We absolutely should be considering native breeds as well as those most suited to local conditions.

Breeds that are native to our exposed uplands will fare better in these areas than breeds that are used to the sunny lowlands of Southern England. They also have a level of disease resistance, which can reduce the need for additional treatment, and can restore a sense of place.

We should be aiming to restore diversity within our landscapes – not just for wildlife, but also for our ancient breeds that have been a part of our countryside for hundreds of years.

If you need more information on rare breeds, RBST provides extensive advice

.

Living free

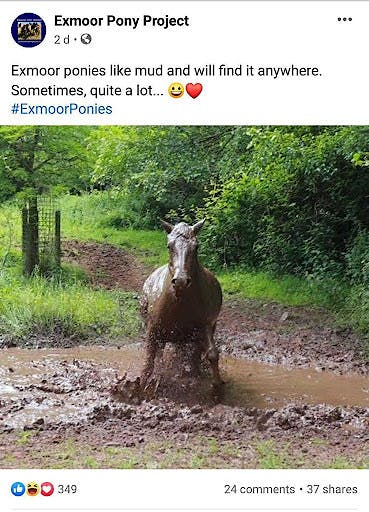

Finally, I just wanted to share this amazing photo from the Exmoor Pony Project .

I had to look twice, as this is a behaviour that I haven’t seen before! It is one example of what could happen when horses are given the freedom to behave on their terms!

Explore our Rewilding Manifesto

We need UK Government to Think Big and Act Wild for nature, people and planet.

Learn more

Our vision

We have big ambitions. Find out what we’ve set out to achieve through rewilding.

Our 2025-2030 strategy