Case study: Revere

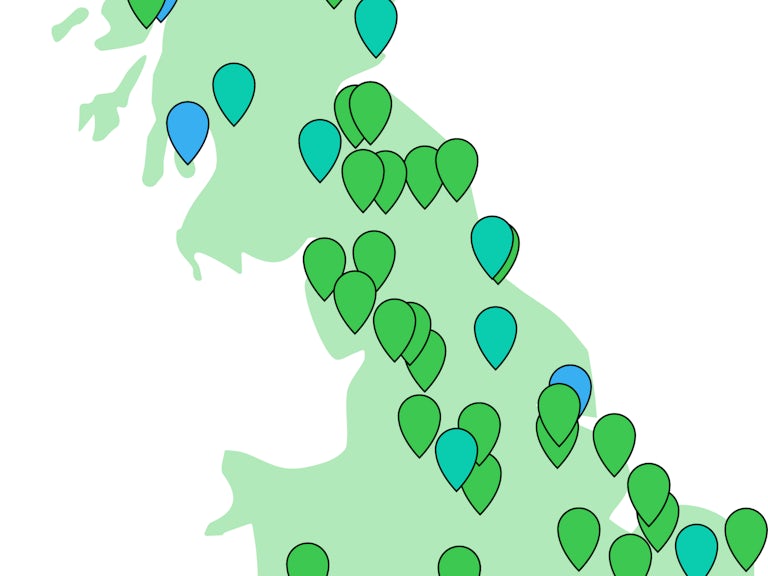

Set up as a unique partnership between global impact firm Palladium and National Parks Partnerships, Revere is working to co-design and aggregate nature restoration projects across Britain’s 15 national parks into financeable portfolios for investors. Community benefits are a central requirement.

In summary

- Project type: Public sector/private investment partnership

- Location: UK-wide

- Current Income: Investor equity, upfront ecosystem service sales

- Projected Income: Carbon credits, water credits, ecosystem service sales

The partnership is a prime example of how private investment can be deployed to advance nature recovery projects on a landscape scale across Britain. Revere works with existing land managers, farmers and communities to design projects that restore degraded peatlands, grasslands, woodlands and wetlands; to raise private capital to finance them; and to generate revenue for all stakeholders by selling ecosystem services.

Revere manages multiple farm and landscape-scale initiatives and collectively finances them with capital from investors — something that’s out of reach for most individual farmers and landowners, given the high legal, professional and transaction fees involved. “Aggregating farm-scale projects makes sense for nature, to create habitat and wildlife corridors across a bigger area, but it also means that farmers and land managers can access private nature finance,” says William Hawes, Head of Nature-based Solutions at National Parks Partnerships.

Nature restoration often requires finance, over and above publicly funded grants, particularly to maintain habitats over multiple decades. The finance can be raised through the forward sale of ecosystem services, with the money raised being deployed to manage the project, pay land managers a fair profit and create benefits for local communities. Alternatively, investors take an equity stake in these aggregated opportunities and get a return from the sale of ecosystem services in the future.

Explore our Rewilding Financing Report

Uncover our blueprint for a game-changing shift in funding and investment for rewilding.

Through Revere’s aggregation model, 30 or so restoration projects are grouped in the Yorkshire Dales, the South Downs and Exmoor, for example, which all generate carbon or other credits. This is key to allowing investors to invest on the scale they require. “The minimum investment for financial investors is often £10 million,” says Hawes. “That funds a lot of nature restoration, but you’re not going to be able to do that on a single farm or single estate. You need a portfolio

of projects.”

Aggregating different projects also helps Revere to attract corporate buyers that have a large ecosystem service credit demand, for example, to achieve a science-based net zero target. “At the moment, the voluntary carbon market is driven by large corporates and institutions that have set sustainability targets as part of an ESG strategy,” Hawes says. “Revere can provide the volume of credits they require by aggregating projects, providing farmers with access to nature markets and an income stream that makes nature restoration viable to them in the long-term.”

Buyers also recognise the value of working with organisations as credible and enduring as the UK’s National Parks. Revere is already selling carbon credits through the Woodland Carbon Code and the Peatland Code and plans to offer its first water credits as part of a project in Windermere to improve water quality and reduce phosphates.

Hawes believes that, where private finance is required, equity is a better fit than loans or other types of debt, because although equity investors often seek a higher return, it’s more ‘patient’ capital. “It takes quite a long time to start generating revenue through ecosystem services. Servicing debt from the point a loan is drawn down requires cash flow and, without revenue, that can undermine the viability of projects,” he says. While private investors are typically very risk averse, and balancing that with nature recovery can be difficult, Hawes thinks they have an important role to play. Not just because they can invest large sums, but because ecosystem service contracts fund habitat maintenance for a minimum of 30 years, and often much longer.

“Supporting the management of these landscapes over that timeframe is just not possible with grant funding alone, which only lasts a few years,” he says. “Farmers and land managers have been operating on short, five to 10-year agri-environment scheme cycles that don’t incentivise the level of management, scale and permanence we need to respond to the climate and biodiversity loss crises.”

Still, Hawes is quick to point out that multiple funding sources are required to fund nature restoration across the UK, including public and philanthropic funding. This factor is particularly critical to de-risking projects at the beginning, he says, when baselining work is being done and the outcomes of rewilding are still uncertain.

“Public grant funding and philanthropic funding are vitally important. If we can get this right, I hope that private finance can be deployed to amplify the impact of existing sources of funding — by carrying some of the risks of the unknown as we learn and try to restore our landscapes,” he says. “I don’t think private finance will or should ever be the sole tool we use, and we need policy and regulation to provide private markets with guard rails, making sure they deliver what we need as a society and are ethical.”

Published as part of our Rewilding Finance report, June 2024.

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network