Meet the rewilders: Gilfach

On a nature reserve tucked away in mid-Wales, James Hitchcock led the gentle rewilding of a hill farm into a nature-rich landscape as CEO of the Wildlife Trust, demonstrating how habitat restoration can be done differently.

This article was published August 2023. On 29 October 2024, James took his passion for rewilding to the next step and moved to a role at Rewilding Britain to lead our policy and influencing work in Wales.

Gilfach is a rare example of a farm that never modernised, so when the Radnorshire Wildlife Trust took it over in the 1980s, they were starting from a fairly high base of natural riches.

Now CEO James Hitchcock and his team are slowly transforming it into an example of how to restore a range of habitats, from wild river valley to wood pasture, working with local farmers to bring benefits for the surrounding community and the wider environment alike.

The story so far

- Who: James Hitchcock, CEO, Radnorshire Wildlife Trust

- Where & when: Gilfach Nature Reserve, mid-Wales, since 1987

- What & how: Restoring nature across a range of ecosystems on a former hill farm; reducing grazing

- Income – current: Wildlife Trust income; some educational /visitor revenue

- Income – future potential: Rural support payments; funding for public benefits such as carbon sequestration, flood mitigation; new forms of food production and marketing

- Ecosystem benefits: Increased biodiversity; native woodland regeneration

A rare gem which escaped modernisation

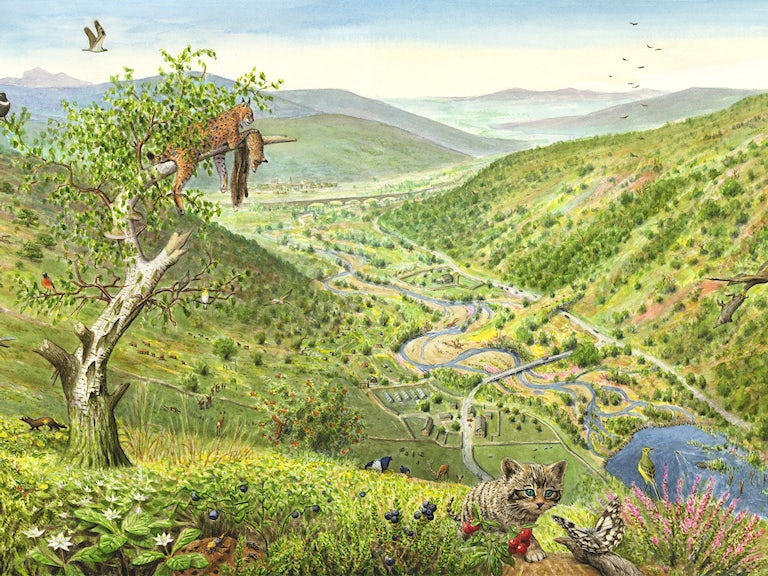

Under the smiling eyes of James Hitchcock, CEO of the Radnorshire Wildlife Trust, a gradual reimagining of an upland landscape is slowly taking shape at Gilfach, a former hill farm nestled on the slopes of the Marteg Valley.

The site is deep in the rural heart of mid-Wales, a few miles from the market town of Rhayader. It stretches from the river itself – tumbling in autumnal spate between fields and woods – over a mix of meadows and up slopes splashed with bracken and rough pasture, together with the remnants of former conifer plantations.

When the Trust acquired the 162 hectares back in 1987, says James, its aim was essentially to restore the farm to a traditional – and nature-rich – landscape. But “over the years we’ve realised it is, and can be, so much more in terms of a showcase for change.” While we wait for the rains to stop over coffee in one of its old barns turned visitor centre he explains that the Trust knew at the time it had got hold of a rare gem of ‘unimproved’ farmland. “For much of the 20th century it had been farmed by the same bloke, Hughsie Lewis, and he’d never adopted the sort of intensive agriculture which became the norm after the Second World War. So nature was in a much better state here.” That said, the land had still suffered from overgrazing, so there was work to do to create more of a resilient landscape for nature.

Gilfach feels remote, but this land has been lived in for thousands of years. Long before the (now disused) Mid-Wales railway cut a path through the valley, it was an ancient route for everyone from cattle drovers to Cistercian monks. To a casual eye, the view may seem timeless, but the area has changed dramatically since Lewis’s day. Intensive grazing coupled with the massed ranks of conifer plantations which have sprung up across mid-Wales has simplified the landscape, and not in a good way.

There’s less variety in farmland, too. “Many farmers around here used to grow their own feed, and have their own market garden, too – or at the least a veg patch for the family”, says James. Some were virtually self-sufficient. “I’ve been to one farm at Tregaron which was lived in by a couple who, right up until the 80s I was told, only ever bought flour, tea and sugar. Everything else they supplied themselves.”

Salmon & dippers, pine martens & kites

Under the Trust’s care, Gilfach is running counter to that homogenisation of the land. A walk through the reserve as the mizzle peters out reveals a patchwork landscape, more typical of hill farms a century ago than today’s countryside, but with nature bursting out all over. The variety of habitats, from the woodland cloaking the river banks and the old railway cutting, over fields spotted with the last specks of summer’s wildflowers, through to the heather and gorse up on the higher slopes, is home to an equally varied wildlife.

James runs off a litany of species spotted here. There are salmon on the river, where the likes of dippers and redstarts swoop on insects. The woods are home to redstart, wood warbler and pied flycatcher; stonechats thrive in the rough pasture, and red kites arc over the ridges. Then there’s meadow pipits, cuckoos, linnets, redpoll, and grey wagtails…

The Rewilding Network

Gilfach is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Butterflies – common blue, green hairstreak, and the increasingly rare small pearl-bordered fritillary – thrive in the flower meadows. “Pine martens are here too”, he says proudly, “and they’re moving over the border into Herefordshire…”.

The clear, clean upland air makes Gilfach ideal for lichen: tree branches abound in furry, fluffy growths which, says James, “include a quarter of all the species recorded in Wales, apparently”.

Put all that together, says James, and the Trust’s monitoring shows that “we have significantly more wildflower species and flora overall than much of the surrounding land, and have a higher density and greater abundance of species than the average [mid-Wales] valley.”

I fell in love with Wales

James himself grew up over in Worcestershire. “I had a very typical English upbringing – you know, cricket, picnics, a bit of fishing, and days out fruit picking, and so just developed a love of nature that way, really.” As a teenager, he toyed with the idea of farming, or forestry, perhaps, “but the careers advice in those days was terrible. Ask them about anything that’s practical or land-based, and they told you not to bother, basically.”

Armed with a degree in physical geography from Plymouth University, he again explored the idea of a career in nature, but was deterred by “loads of narrative about it being such a tough sector to crack”. With his boyish enthusiasm shining out of bright blue eyes behind his specs, it’s hard to imagine him being easily put off. Nonetheless, he ended up “working for a year in a job just for money” before he’d had enough, and went to volunteer at the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust. “And that was it! I knew from the first week that this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

A flurry of short-term contracts followed, including one with the RSPB on the north Welsh coast, “when I totally fell in love with Wales”. Through positions with several Wildlife Trusts, he gradually developed something of a specialism in nature reserve management, “and then ended up here [at Radnorshire], in my first CEO role – and it’s just great to be back in Wales!”

Encouraging biodiversity at Gilfach over the past three decades hasn’t required too much in the way of sweeping interventions, however: the unmodernised state of much of the land means it started from a relatively rich ecological base. Gesturing at the slopes above the Marteg, James points out the biggest single change: “We’ve cleared some of the conifer plantations, and replanted some with broadleaves, although natural regeneration plays a part too.” Silver birches springing up the hillside among the bracken bear witness to the change.

Over time, there’s even the beguiling prospect of something approaching temperate rainforest taking root – once a natural habitat in the region, but one that has shrunk to tiny refuges, in a country where around 70% of all forest cover in public ownership in Wales is now conifers.

Mimicking natural processes

And it’s up on those slopes where another transformation is taking place. After buying Gilfach, the Trust fenced the land off to cut down on grazing animals coming onto the property, while continuing to rent out fields for neighbouring farmers to run their livestock. While that took some pressure off the ground and helped natural regeneration, they’ve now gone further. Working with a local farmer who’s committed to more sustainable husbandry, the reserve is now hosting around 60 Welsh mountain sheep, together with a small herd of cattle – Welsh White and Galloways.

These are “fitted with GPS collars, which means we can control exactly where they graze, and for how long”, James explains. By moving them around from one place to another in short rotation – so-called ‘pulse’ grazing – the Trust can ensure the animals break up the grass and soil and keep the bracken in check, so encouraging a richer variety of plants and wildflowers, and natural regeneration of native trees. And all, says James, “with a minimum of human intervention” – which makes it all the more affordable, too. He contrasts it with “the intensive nature reserve model, where you all gather around a dwindling number of species in very managed and highly prescriptive setups. If you can shift to mimicking natural processes using large herbivores, that’s much, much cheaper – and you can do it at scale.”

And it’s clearly, visibly working. The contrast between the sheep-cropped sward on the far side of one of the reserve’s boundaries with the richer, messier mix of growth within Gilfach is striking.

“If you can shift to mimicking natural processes using large herbivores, that’s much, much cheaper [than the intensive nature reserve model].”

He’s also keen to work more with neighbouring farmers as the much-anticipated new agricultural support schemes kick in to replace the basic payments subsidy and reward environmental protection work, such as the Sustainable Farming Scheme (SFS, the Welsh version of ELM). “Farming Connect [the Welsh Government’s advice service] says that requests for advice on biodiversity, on carbon, and sustainability in general have just gone through the roof lately, and they just can’t meet the demand at the moment”, says James. “I think we’ve got really useful skills and experience on all that which we can share with farmers.” It needn’t be just one-way, either, he adds. “We can learn from them as well.”

Meanwhile he stresses that simply by carrying on what they’re already doing, Gilfach is producing the sort of public benefits – not just in biodiversity, but carbon storage, and flood mitigation too – which the government wants to incentivise farmers to deliver. In time, they hope to be able to measure and monitor specific progress on all this, to back up with crunchable data what they are sure is already happening.

Future perfect

Before we wrap up, I ask James what the future for Gilfach looks like – 50 years from now, say, when leaning on a stick he shows his grandchildren the fruits of his labours. It’s clear he’d given this some thought…

“We’ll have some cattle on the hills, just enough to maintain a sort of wood pasture, with oak and rowan among the heather, keeping the bracken suppressed. Species such as hen harrier will be returning. Down in the valley, there’ll be patches of short-grazed turf, with wax caps and coral fungus. The river will be taking a more natural, braided course, rather than flowing solely through a single channel, and in the long grasses there’ll be globe flowers and water voles. The woodlands will be full of pied flycatchers and redstarts and wood warblers.”

“Society will have changed, too. People will be able to cycle out safely from Rhayader, and spend the day immersed in nature. And this won’t just be an immensely pleasurable experience for them: they’ll also know that this place is performing absolutely vital functions like sequestering carbon, storing water and alleviating flooding.”

I compliment James on the detail of his vision. “Well”, he responds, “as conservationists, we spend a lot of time saying ‘we don’t like this, this is bad, that should stop’… It’s a staple of campaigning, and that’s all well and good. But we’ve also got to say, ‘This is what the future could look like; this is what it could be like to live in it. This is how it could feel.’”

Published August 2023. On 29 October 2024, James took his passion for rewilding to the next step and moved to a role at Rewilding Britain to lead our policy and influencing work in Wales.

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network