Meet the rewilders: Haweswater

In the heart of the Lake District, the RSPB’s Lee Schofield is spearheading an ambitious project that’s showing how upland farming and nature recovery can go hand-in-hand.

When the RSPB took on the tenancies of two hill farms in the Lake District, to demonstrate the potential compatibility of sustainable hill farming with nature recovery, Lee Schofield and his team had to battle against a strong reluctance to change established farming practice.

Ten years on, a rewiggled river, re-emerging wild flowers and regenerating woodlands have proved that restoring nature can transform a landscape – and provide benefits for people and wildlife downstream, too.

The story so far

- Who: Lee Schofield, Wild Haweswater (a partnership between RSPB and United Utilities)

- Where & when: Naddle and Swindale farms, Lake District, since 2012

- What: A partnership to create a landscape of thriving upland wildlife alongside sustainable farming

- How: Reducing stock density, replanting/conserving native trees and flowers, river rewiggling, restoring peat bogs, introducing large herbivores

- Income – current: Public subsidies/stewardship payments; farming; small-scale tourism

- Income – future potential: ‘Memorial wood’; conservation training; eco-tourism; ELM-style support payments

- Ecosystem benefits: Nature recovery on depleted hillsides; restored riverine landscape; flood prevention and water quality improvement

A baptism of fire

Lee Schofield had enjoyed a varied career in conservation by the time he took up his position at the RSPB’s Wild Haweswater reserve. He’d worked with local communities, including farmers, elsewhere in Cumbria, and was enthusiastic about the journey ahead.

The RSPB had just taken on two loss-making farm tenancies at Haweswater from the landlord, United Utilities and, as Site Manager, Lee would be leading a project which, in his words, aimed to “get a better understanding of hill farming systems from the inside – of the economics as much as the ecology.”

But nothing prepared him for the difficulties he ran into at early encounters with some of the local sheep farmers, when he set out his vision for sustainable livestock rearing across the Haweswater hills.

In his book, Wild Fell, which includes a disarmingly frank account of his early struggles, he recalls the reaction at one meeting. “As the farmers began putting up their hands, we were accused of dismantling thousands of years of custom and practice, of land abandonment [and] rural depopulation, of not being neighbourly, of removing a stock of sheep that could trace their ancestors to the time of the Vikings, [and] reducing the nation’s ability to feed itself…”

He remembers sitting in his car after one such meeting, talking to his wife on the phone, seriously considering throwing in the towel. “I came out of that room just feeling totally outnumbered.” In a way, he’d become a focus for resentment at any change seen as coming from outsiders – a prejudice confirmed, Lee says, “as soon as I opened my mouth”.

His accent betrayed his southern origins; he was born and raised in rural mid-Devon, where he enjoyed quite a “free range” childhood. “I was really lucky to have so much nature around me.” Leaving the Devon countryside behind to study Zoology at university, followed by a Masters in Ecological Management, “made me realise that nature needed more protecting in order for more people to have those kinds of experiences that I’d been lucky to have.” And so – after a brief spell flirting with a future as a rock musician – a career in conservation beckoned.

In time, that took him to Cumbria; his wife is from the county, and as their first child came along, it made sense to be near her family. A spell with the local Wildlife Trust, leading the restoration of a raised bog on the Solway, served as a good apprenticeship for the Haweswater job, as it included partnering with local farmers who held commoners’ rights.

At least, it seemed to, until he ran into that wall of hostility. Even the then local MP, Rory Stewart, at first supportive, joined in the pile-on. Much of it was, of course, based on sweeping misapprehensions. “There was so much rumour and speculation – most far from the truth.” In reality, the RSPB’s aims were deliberately modest: to prove that it is possible to continue to farm livestock on the fells while also helping the natural environment to recover and flourish.

“When it comes to the people who are already there, working on the ground, we need to bring them along with us.”

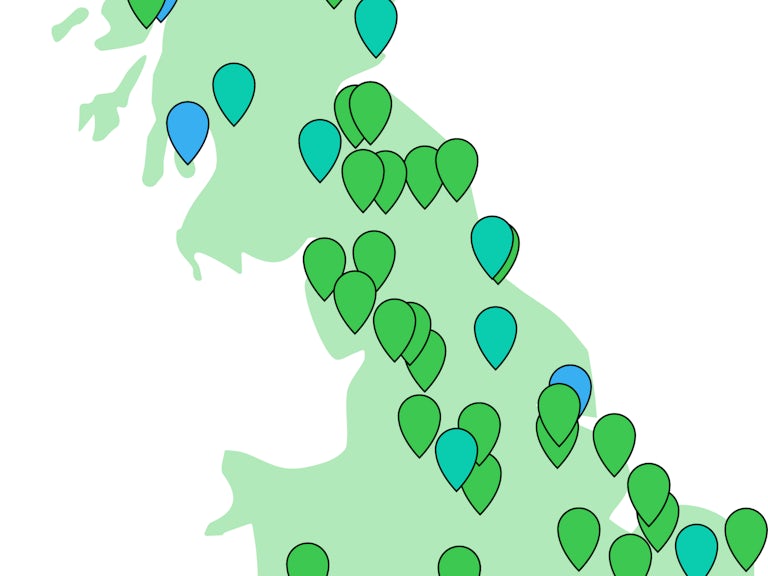

The Rewilding Network

Haweswater is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Restoration, not revolution

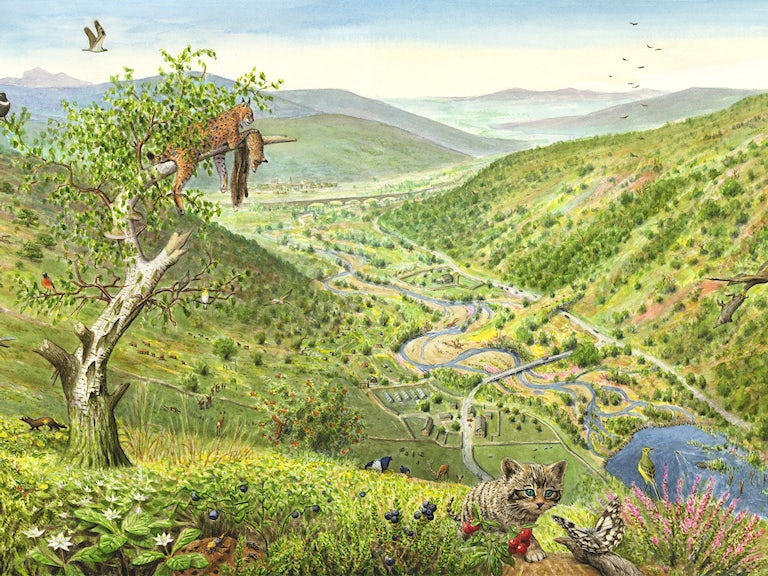

On the wall of the meeting room at Naddle Farm – Wild Haweswater’s base – there’s a bird’s eye view of what the area will look like when its plans come to fruition, alongside one showing its current state. The difference isn’t that dramatic. More scrub, more trees, more birds of prey arcing over the landscape – but it’s still recognisably Lake District. Far from clearing the land of all sheep and seeing it revert to thick forest, the plan is to reduce the stock to a level compatible with nature recovery.

Some visitors, says Lee, are a little disappointed that it doesn’t depict more of a revolution. But that’s to underestimate the changes that are already underway. Where once there were bare slopes, sheep-cropped down to the turf, now they are sprinkled with bushes and young trees, some planted, some naturally emerging. In the tree nursery at Naddle Farm, seedlings of juniper, aspen, alder, willow, birch and oak are carefully nurtured, ready for planting out on the fells.

Some of the Lake District’s most fragile flowers, including the rare pyramidal bugle, are making their way down the slopes from precarious refuges among the crags. Lee, who is as much of a botanist as a birder, is particularly proud of this gradual ‘reflowering’ of the landscape.

Meanwhile, he and his team are also introducing limited numbers of cattle (hardy Highland and Belted Galloways) and fell ponies. These are both ‘beneficial herbivores’, which can help open up space for wild flowers and trees to break through bracken and coarse grasses, and generally mimic the effects of the wild cattle and ponies which would once have roamed these hills.

But perhaps the most impressive change, says Lee, has been the rewiggling of the Swindale Beck. Running through one of the most gorgeous valleys in the area, the beck had been forced into a single fast-flowing narrow channel many years ago. As well as leading to increased flood risk, this had stripped out all the gravel on which salmon depend to lay their eggs.

Now it’s been allowed to find its natural path again, meandering over the valley floor, full of riffles and pools – and here the difference is indeed dramatic. Salmon are spawning again in Swindale; increased numbers of invertebrates provide food for birds such as dippers, and otters come hunting up the river. The water meadows sport a profusion of wild flowers.

“Salmon are spawning in Swindale again, and the meadows sport a profusion of wild flowers.”

It’s an object lesson in what happens when nature is allowed to do its own thing, says Lee.

“Where you have physical diversity, you get ecological diversity – the whole thing just builds itself back together again, and comes back to life.”

None of this would be possible without a fairly dramatic reduction in sheep numbers – and that’s not always popular with the neighbours. The fells for the most part are unfenced: sheep have to be laboriously shepherded onto a particular patch, yet once established, they’ll typically stay ‘hefted’ to it, and not stray onto another flock’s ground. But if any one farmer suddenly reduces their stocking density, then other flocks will drift more widely – making a lot more work for the neighbours..

To overcome this objection, Lee and his RSPB colleagues had to get special permission to put up fences – and that meant treading on the toes of another powerful local interest group, the landscape lobby. The Lake District landscape – however unnatural – is recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While farmers quite like the fences, the landscape heritage lobby is much more sceptical. Hence, again, the RSPB’s aim is to tread lightly, finding ways to help nature recover without revolutionising either the local economy or its landscape.

What about dry stone walls – wouldn’t they be preferable? “Yes sure”, says Lee – “if you’ve got the budget of a small housing estate to play with.”

Economics and ecology

Economics constrain choices – not only for Wild Haweswater, but its neighbouring farms. They all essentially depend on public subsidy, Lee explains – whether it’s the Basic Payment Scheme, or environmental grants such as the various stewardship programmes for which the RSPB farms qualify. The direct income from sheep alone is hardly ever sufficient for a farm to break even. Indeed, the input and labour costs alone usually outweigh it, as was the case when they took on Naddle and Swindale.

Lee is optimistic about the potential of a shift in the subsidy system, towards schemes which reward landscape recovery. Wild Haweswater is taking part in one such pilot project under the ELM (Environmental Land Management) scheme, which could unlock substantial funding in the future. Such a shift will inevitably drive the sort of change which could yet bring even conservative farmers round to a more sustainable mindset, he believes.

It’s still not yet all sweetness and light between them and Wild Haweswater, but a decade on from those initial bruising encounters, “we have kind of become part of the furniture… Even our strongest opponents accept that we’re not going anywhere.” Meanwhile, Lee is cheered by the way other landowners in the region are already transforming their holdings, including the Lowther Estate, “which is fast becoming the ‘Knepp of the North’”. They are collaborating together, along with United Utilities and Natural England, on a new nature restoration project, the Cumbrian Landscape Partnership, under the auspices of the Endangered Landscapes Programme.

He’s cheered, too, by the direct employment benefits that Wild Haweswater and associated projects are bringing to the area. “We started in 2012 with a team of four. By March 2023, that will have grown to 22.”

Lee readily admits that he’s learned lessons, too. “I think when I started out, I was probably quite hard line and thought we need to change everything right now. Now I recognise that, actually, when it comes to the people who are already there, working on the ground, we need to bring them along with us.”

Meanwhile, he says, with two young children, he’s driven on by a fear of a future where, unless we act fast to stop it, “the great dwindling of nature which is happening all around us” will just continue unabated. But at the same time, he’s heartened by some of the changes his work has already brought about: the flowers returning to the fells, the insects reappearing, the salmon in Swindale… “Seeing that whole web of life begin to re-establish itself is just hugely, hugely satisfying.”

Published January 2023

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network