Meet the rewilders: Highlands Rewilding

Eco-entrepreneur Jeremy Leggett is at the head of a rewilding business aiming to prove that nature restoration in Scotland can mean ‘repeopling’ the Highlands and putting community prosperity at its heart.

After a successful career in renewable energy, solar entrepreneur Jeremy Leggett has joined forces with local activists and an array of expert ecologists to launch Highlands Rewilding.

With landholdings encompassing everything from cattle pasture to native forest, peat bogs, moor and the Loch Ness shoreline, it’s ideally suited to mapping the potential for nature restoration at scale.

The story so far

- Who: Jeremy Leggett, CEO; Kirsty Mackay, Head of Operations

- Where & when: The Highlands, Scotland, since 2021

- What & how: Restoring natural landscapes, exploring regenerative farming, working in partnership with local communities and encouraging local investment

- Income – current: Investment income

- Income – future potential: Expert consultancy monitoring rewilding impacts, biodiversity and carbon mapping; natural accounting; ecotourism and ‘away days’; food production; sustainable housing

- Ecosystem benefits: Restored native woodland, peat bogs and water courses; nature recovery on overgrazed farmland; revival of local wildlife species; carbon sequestration

The campaigner turned entrepreneur

“I’ve always been a climate campaigner, even when I was posing as an entrepreneur”, says Jeremy Leggett, as he looks out over the slopes of Bunloit, tumbling down to Loch Ness.

An unlikely one, you might think, given that his early career, as an academic geologist at Imperial College, included researching shale deposits – work funded by BP and Shell. But it was such closeness to the beating heart of fossil fuels that helped trigger his first career shift. Alarmed at the growing evidence of global warming, he turned his back on the sector in the most emphatic way, joining Greenpeace as a climate campaigner in 1989.

“Rewilding, or nature recovery, or whatever you want to call it, doesn’t come with a handbook.”

Jeremy Leggett

Then his entrepreneurial instincts sparked into life, and in 1997 he founded Solarcentury – which helped blaze a trail for commercially successful solar power in the UK and abroad. Along the way, he acquired a clutch of awards for green entrepreneurship, served on advisory boards for the UK Government and the World Economic Forum, launched SolarAid to deliver solar power to poor communities in the global south, wrote books warning of the twin risks of oil depletion and climate change, and lectured at Oxford, Cambridge and elsewhere. Phew.

After he sold Solarcentury to Europe’s largest renewable energy generator, Statkraft, in 2020, he could well have felt entitled to put his feet up, now in his late sixties…

Not a bit of it. Instead, in another career switchback, he bought not one but two estates in the Highlands, and set about launching a new business designed to have as positive a disruptive boost for rewilding as Solarcentury had for green energy. The two sectors sound a world apart, but for Jeremy there’s a powerful connecting thread.

“I’m excited by [a combination of] the start-up, entrepreneurial environment, and serious breakthrough revolutions. Solar was a serious breakthrough revolution, and Solarcentury played its part in that. But no matter how successful we are with all that good green energy stuff, we still have to take carbon out of the atmosphere. And we have to do it in a way that helps nature recover.” Cue a rewilding venture as catalyst for the next disruption.

Beldorney and Bunloit

So the next question was, where? And the obvious answer? “Scotland: it’s got a lot of land that’s fit for purpose. And I love the Highlands – my parents used to bring me up here youth hostelling when I was a kid.”

Prospecting around for likely candidates, he found two contrasting estates – Bunloit, a mix of native woodland and conifer plantations, along with peat moors, above the shores of Loch Ness; and Beldorney, in Aberdeenshire – mainly grassland, much of it recently intensively grazed. Drawing on some of the cash from the Solarcentury sale, along with around 50 private investors, he was able to acquire both during 2020 – 21.

Now they’ve been brought together under the auspices of Highlands Rewilding

Ltd. Its purpose: “Nature recovery and community prosperity through rewilding taken to scale in the Highlands of Scotland.”

Put like that, it sounds almost straightforward, yet the reality was anything but. “There’s no obvious roadmap, like there was [when I started with] solar”, says Jeremy. “Then, we knew what we needed to do: knock fossil fuels off their perch and replace them with renewables. But rewilding, or nature recovery, or whatever you want to call it… it doesn’t come with a handbook.”

So rather than pitch in with detailed plans, the project started off with “a lot of learning, and a lot of listening. I had to educate myself, and talk to the experts – as many as I could.” And there was a lot of listening to local people too.

Well aware that, as an English entrepreneur with no particular links to the Highlands, he might be treading on sensitive toes, Jeremy and his team were careful to consult local opinion before unveiling any grand strategy.

Early recruitment decisions did no harm here. One of the first hires was Kirsty Mackay, now Head of Operations. Vivacious and energetic, she talks at a hundred miles an hour, and a clear enthusiasm for her work tumbles out through her words.

The repeopling enthusiast

Growing up on a Highlands croft had instilled a deep love of nature, which a degree in Biology did nothing to dispel. After a couple of years working in Australia, she returned home to the croft just as Covid struck. Many months casting around for work culminated in her seeing an ad for executive assistant to Jeremy, and she soon took on more responsibilities. With her impeccable local credentials, this unsurprisingly included sounding out the locals.

“From the start”, she says, “we made sure we linked nature recovery with community prosperity. Some people have the idea that rewilding is a modern form of Highland clearances. And I feel very strongly opposed to that notion, because in truth what we’re doing here is the exact opposite! For us, rewilding is all about repeopling the land. Creating jobs, creating new enterprises, and still having an element of food production, which we absolutely need.”

The ‘repeopling’ is already under way. “This [Bunloit] estate used to have no-one working on it; now there’s around 20.” The goal isn’t just direct employment, either. Kirsty points out ruins of abandoned crofts, evidence that the land was once indeed more ‘peopled’ than now, and which they’d love to restore and see reoccupied.

So how did local people react to the rewilding incomer? For the most part, very favourably, particularly at Beldorney, as Jeremy explains: “I wrote to the community association, and said, ‘This is what I’m up to – but I need lots of help and advice on all the specifics before I do any major interventions. Can we meet?’ They copied the email to the entire community, and I got deluged with replies.” Meetings followed, and the reaction “was amazingly positive.”

It helped that Jeremy’s outline thoughts chimed with the aims of the local Cabrach Trust , which works to bring people back to the area, create affordable housing and boost tourism. The Trust is an enthusiastic supporter of a new ‘Forest of Hope’, comprised of carefully selected native broadleaves, which will be planted across a swathe of the estate, and – in partnership with other landowners – extended up the Deveron Valley.

Over at Bunloit, meanwhile, the only really significant murmurs of dissent have come from a small minority of residents concerned at the potential impact of early plans to work with a nearby sustainable timber company and build a few affordable eco-houses and workshops for local people. More encouragingly, Kirsty, Jeremy and the team have made strong links with the local school, running outdoor classrooms on the land.

“For us, rewilding is all about repeopling the land. Creating jobs, creating new enterprises, and still having an element of food production.”

Kirsty Mackay

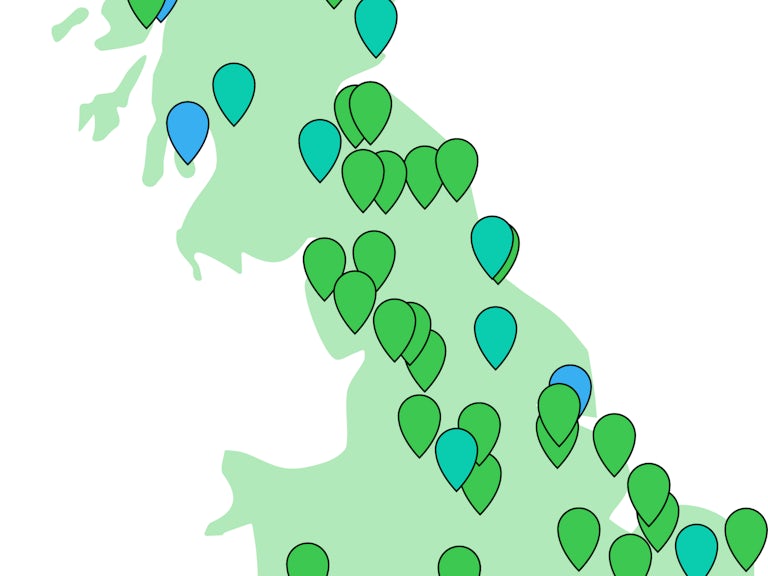

The Rewilding Network

Highlands Rewilding is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Mapping the potential

They’ve also employed experienced locals as estate rangers. Two of them, Scott Hendry and Daniel Holm, walk me round some of the Bunloit estate. It’s a mixture of conifer plantations and native woodland. Some of the plantations have already been felled: “It’s the one thing all the experts agree on”, says Jeremy, “clear the conifers!” – although as Daniel points out, leaving a few in place makes sense to provide winter shelter for birds.

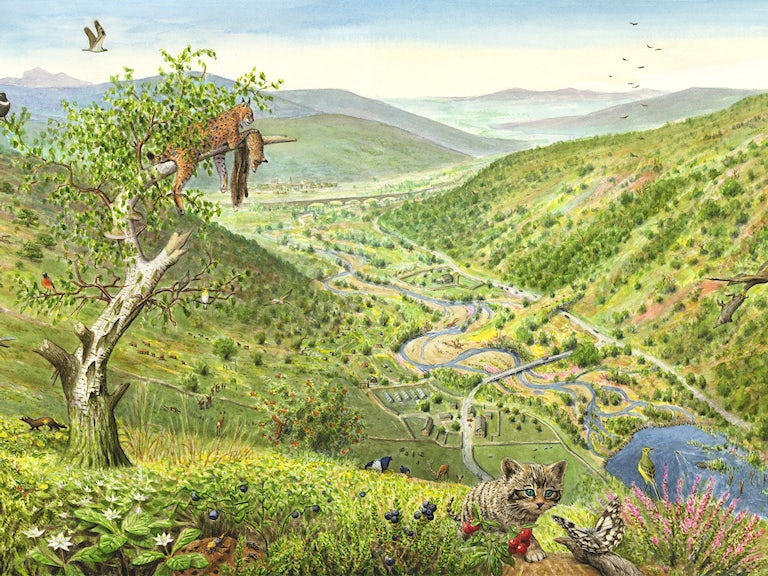

The natives include rainforest-like swathes of oak on the slopes above the Loch, and patches of open woodland, home to pine martens and red squirrels, rich in moss and lichen, scattered with ancient Scots pines. You get a sense of what the land wants to look like in the open rides which were left as firebreaks within the plantations. There, an array of wild flowers – common cow wheat, heath bedstraw, eyebright and bilberry – spring up, like ghosts of a lost landscape which the new owners are keen to recreate.

The ghosts are in the names of local landscape features, too. Scott points out the denuded slopes of a hill called Darroch – the Gaelic word for an oak wood. Other Gaelic place names nearby mention wolves and wild cats – echoes of animals once common in the land.

Meanwhile, on the 21st century ground, some initial work is underway. At Beldorney, which had been “grazed to extinction” as Jeremy puts it, sheep have been replaced by a small number of cattle using all-year-round mob grazing methods, which both break up the turf to stimulate a variety of new plant growth and allow the land to recover in between. Over at Bunloit, a local farmer who was grazing sheep on part of the estate has agreed to swap them for Highland cattle, on the same basis.

Longer term, there are plans for agroforestry and horticulture, too, perhaps some renewable energy, opening up the land for joint ventures with local communities. This could include creating small-scale sustainable communities on the land – a 21st century hi-tech, eco-positive version of the crofts which were once scattered over the Highlands.

But the bulk of the early effort is on mapping just what the land holds – and its potential. Highlands Rewilding has assembled an impressive array of experts to carry out studies on soil and biomass carbon and biodiversity, including using sophisticated environmental DNA techniques, along with a range of other baseline assessments.

It’s already thrown up some intriguing findings: Bunloit’s extensive peat bogs, for example, far from being a carbon sink as is commonly supposed, are actually a net source of carbon emissions. Why? Because they’ve been drained so much, partly for forestry, that they’re drying out, releasing CO2 as they do so. So bog restoration emerges as a top priority.

Such thorough ecological mapping is a key part of Highland Rewilding’s emerging business offer. With all their accumulated expertise, the team and their advisers are well placed to provide similar services to the increasing array of rewilding projects springing up across the UK and abroad.

“I’ve been really lucky in attracting some serious science and data firepower”, says Jeremy. “So I’m really hoping that, as well as making this an ethically profitable business, we’ll also be able to demonstrate that the right kind of land management can deliver rock solid, verified, triple A‑rated uplifts in carbon [storage] and biodiversity.”

Again, he says, there are parallels with his days as a solar pioneer. “Much of the challenge back then was verifiability, too: people just didn’t believe that solar could do any heavy lifting. We had to demonstrate that it could – and we did.” Now, he says, they have to do the same with rewilding – and do so in a way which has real credibility. And there’s an urgency to it, he adds. “There are already so many cowboys out there: brokers leaving business schools and coming up with business plans to broker this and broker that and trade carbon off into the future… We need to knock the props out from underneath the cowboys.”

As a business offer, this data gathering and interpreting expertise will complement income from the eco-tourists that the estate is well placed to attract: people who want to see rewilding under way, stay in some of the converted cottages and grander houses, spy out red squirrels, pine martens and wild boar from woodland hides, see eagles soaring overhead, and spot rare butterflies.

An additional draw could come in the shape of a new acquisition, the Tayvallich estate, which holds out the possibility of restoring and extending fragments of Atlantic temperate rainforest.

Put all that together, and the team is confident that they now have a detailed business plan fit for investment, and have launched a crowdfunder , with a particular aim of attracting local people, and those with an affinity to the Highlands, as shareholders. With that in mind, the minimum investment has been set at £50. This funding round closes at the end of April 2023.

Kirsty enthuses about the potential. “What we can do here is show how managing land for nature recovery can be economically viable, and then get other landowners on board as well. Yeah, the possibilities are really exciting: this can help create a Scotland where nature is thriving, where people are thriving, and their businesses are as well.”

“You know, before I started working here, I was very down about the state of the world. But now I’ve met so many people doing such good stuff – well, it just can’t help but give you hope. Lots of hope.”

Published in January 2023

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network