Meet the rewilders: Langholm

Amid the moors and valleys of the Southern Uplands, a town once known for its textile mills has found new life and purpose thanks to one of Scotland’s largest community land buyouts.

Natural regeneration normally describes an ecological process. But in the case of Langholm, it could also stand for the rebirth of the town’s prospects. After years of decline, its bold decision to buy out 4,000 hectares of a landed estate on its doorstep holds out the prospect of recovery for both nature, and the town’s economy.

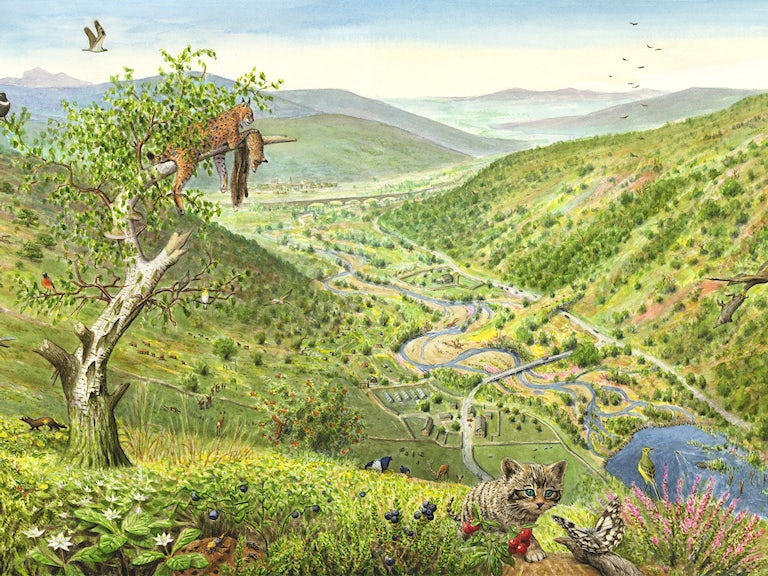

The buyout has given birth to a brand new conservation area, the Tarras Valley Nature Reserve

– a rich kaleidoscope of habitats. And at the beating heart of the whole project are two contrasting, dynamic and determined women – Margaret Pool and Jenny Barlow.

The story so far

- Who: Langholm Initiative: Margaret Pool (former Chair); Jenny Barlow (Estate Manager)

- Where & when: Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, from 2019

- What: Community buyout of former grouse moor to be managed as a nature reserve

- How: Clearing conifer plantations; creating new woodlands; conserving precious habitats and fostering nature recovery, planning new sustainable economic activities

- Future potential income: Tourism, educational and research activities, regenerative farming, possible renewable power

- Ecosystem benefits: Nature recovery on over-grazed hillsides; conservation of rare valley woodland; peat restoration; wetland conservation; soil recovery; flood prevention

The heart of the community, Margaret Pool

As chair of the Langholm Initiative (until late 2022), Margaret Pool has been at the heart of the buyout success.

A lively, wiry, twinkly lady, she’s lived in Langholm for nearly 60 years, but first came to know the town on childhood holidays. “It was back in the day when most people didn’t have a car, so we came by bus from our home in Falkirk. Three buses, actually! And that in itself was an adventure for a young girl like me.”

Those summer visits coincided with a Langholm tradition known as the Common Riding, an annual fair celebrating the townsfolk’s success, back in the mid-18th century, in winning common rights over an area of land managed by one of Scotland’s largest private landowners, the Duke of Buccleuch. “I got completely hooked on the Common Riding”, Margaret recalls. “It was so exciting!”

She later married a Langholm local, and settled in the town. Yet her time there has coincided with its economic decline. “It used to be known as a ‘muckle toon’”, she recalls, using the old Scots phrase implying a bustle of prosperity, thanks to its numerous thriving textile mills and associated crafts. Since the seventies, these have gradually closed down. As employment prospects fade, so does the population. “When I first came here, we had a really thriving high street. Now the young people go away to college, and they don’t come back.”

In recent years, too, the Buccleuch estate had been winding down its activities. “They’d had a very heavy staff at one point”, recalls Margaret, “farmers, gamekeepers, tradesmen… You could learn all sorts of skills. And they provided houses, too…”. As that dwindled away, the town lost another source of jobs.

“We’ve already created five new jobs, we’re using local contractors, we’re getting more visitors to the town.”

The first buyout

The estate had been divesting some of its lands for a while, but when the news came through in 2019 that a little over 2,000 hectares of the Tarras Valley was up for sale, it was “a bolt from the blue”, says Margaret. She and others in the town immediately spotted an opportunity to turn the community’s fortunes around.

Under Scottish law, communities can bid to buy land that comes on the market in their area, and can benefit from government assistance in doing so – if they can prove there’s local backing. “We were given a month to show that 10% of the population were behind us”, says Margaret. “So we went out with our clipboards and we knocked on doors – and had 20% within a fortnight!” Then came the hard bit: putting together a viable business model for the land – and agreeing a valuation with Buccleuch.

But they weren’t alone. Together with her colleagues in the Langholm Initiative, project leader Kevin Cummings and vice-chair John Hanrahan, Margaret was able to draw on the experience of earlier successful buyouts. They could also call on the advice of a host of sympathetic environment and wildlife groups, who were excited about the potential of restoring this mix of moor, woodland and the Tarras Water ecosystem.

The estate proved to be sympathetic vendors, too, thanks in part to their close association with the town. “We’d been taking school groups up to the moor, with Buccleuch’s blessing, for a while, for nature study and so on”, says Margaret, “and we’d got to know their estate managers.” They agreed a valuation of £3.8 million – of which the Scottish Land Fund stumped up £1 million.

With a tidy sum still to raise in just six months, Margaret and her colleagues staged a skilful fundraising drive, talking up the prospect of a run-down town coming together with a bold plan to reclaim their ‘backyard’. Donations of up to half a million pounds came in from the likes of the Bently, Carman Family and Garfield Weston Foundations, along with the John Muir and Scottish Wildlife Trusts, Rewilding Britain, RSPB Scotland, and Trees for Life.

Just days before the deadline, “it was still touch and go”, but a final flurry of crowdfunding pulled in £50,000 from the public, including some who had family ties to Langholm, as well as residents themselves. Then almost at the last minute, the Woodland Trust, who had been hugely impressed by the quality of the ancient woods bordering the Tarras, came up with the £200,000 needed to take them over the line.

So suddenly, this small community development initiative found itself the custodian of a richly varied landscape. Which is where Jenny Barlow comes in, as the first estate manager of the newly created Tarras Valley Nature Reserve.

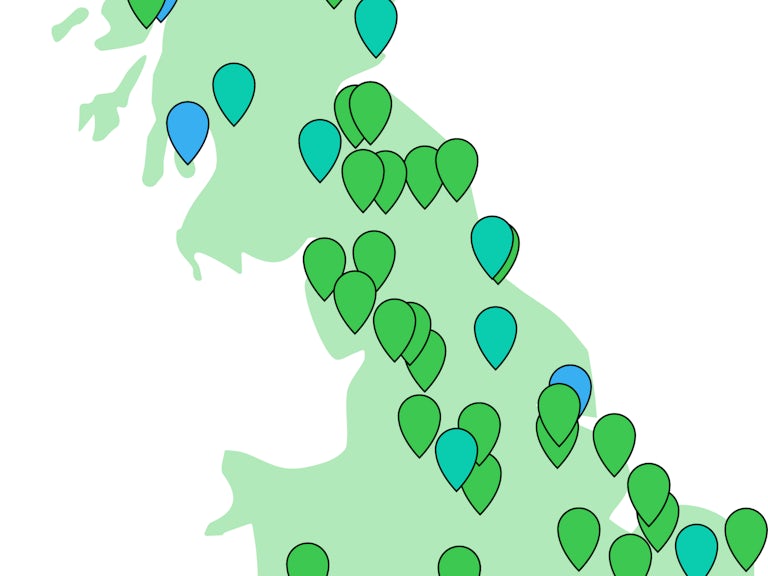

The Rewilding Network

Langholm is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

The Estate Manager, Jenny Barlow

Brought up in Sunderland, Jenny bubbles with an infectious enthusiasm for everything from ancient alders and flycatchers to new ways of engaging with communities at the grassroots. That’s just as well, as her role is equally wide-ranging, embracing forest management and timber sales, economic regeneration plans, wildlife recovery and – inevitably – fundraising.

After studying Landscape Architecture, she’s worked across a whole range of sectors – wildlife management, corporate sustainability, a spell at the Environment Agency and community engagement. “So when this job came up, it just pulled together all the things I’m passionate about – environment, yes, but also community participation – and how to do it differently.”

Her accent gives her away as an incomer, though, she says, “people couldn’t have been more welcoming”. As a woman working in what is still largely a man’s world of estate management, she needs all her wits about her to prove that she can make change happen. And to do so at the pace needed to demonstrate to donors and locals alike that the buyout was no act of whimsy.

A second victory

That pace picked up in 2021, when the Buccleuch estate released a further 2,100 hectares for sale for £2.2 million, encompassing not only a swathe of valley, but hill farmland and much more exposed moorland. “It includes virtually the whole of the Tarras catchment”, says Jenny, “which from an environmental point of view makes it incredibly exciting”, as it now contains a wide range of habitats.

But first, she had to pull the funds together – and all while juggling the rest of her work. “One moment I’d be wrestling with funding bids; the next, I’m talking to a forestry contractor about taking down timber; looking for the best price.” That variety suited her sparky enthusiasm. “It’s nice to be around people every day that want to make a difference. It is genuinely a case of ‘we’re all working to do something really incredible here!’”

That said, she adds, “it’s been a steep learning curve all right – it got pretty intense at times.” All the more so when, as the deadline for finalising the sale approached, it looked once again like they might fall short. But Buccleuch “were really supportive”, says Jenny, even to the extent of pushing back the sales deadline by a couple of months. A last-minute surge of donations helped take them over the line, and at the end of July 2022, the land was secured.

“The towns downstream face something of a flood risk… restoring peatlands, planting forests, conserving wetlands, will all help slow the flow of water.”

Rebooting the region

Now Jenny is faced with the tantalising task of planning a strategy to manage everything from the sheep-cropped uplands, down to the ancient oaks and alders, draped with moss and lichen, bordered with peaty water meadows, and cloaked in wildflowers, which lie along the lower reaches of the Tarras.

Get it right, she says, and the environmental benefits will extend way beyond Langholm. The towns downstream on the Solway catchment face “something of a flood risk. So anything we do up here by way of restoring peatlands, planting forests, conserving wetlands, will all help slow the flow of water.”

Like many rewilding projects, the most obvious initial signs of change on the ground have been the felling of old conifer plantations. This can leave a scar of bare earth which people find offputting, to say the least. But nature had lent a hand in the form of Storm Arwen, ripping through the stands of Sitka spruce and larch and leaving many positively unsafe – so in Langholm at least, it proved popular. “Now we’re working with the Woodland Trust to create a new large wood of native broadleaves.”

It’s not just about the environment; there are people on the estate, too. Several farms and houses have sitting tenants, so Jenny and Margaret have been reassuring them that their homes and livelihoods are safe. And the wider social benefits are just beginning, says Jenny. “We’ve already created five new jobs, we’re using local contractors, we’re getting more visitors to the town.”

As a next step, they’re exploring a whole range of economic potential. Ecotourism, of course, “but we’re not going to rely on that. We’re looking at lots of different ways to make it economically resilient. People are getting in touch all the time, looking to work with us.” Among the possibilities are solar power plants, carbon credit sales, education and training visits, and research partnerships with academic institutions, including cutting-edge tech. Jenny enthuses over the prospects of being “a pilot site for an app to help land managers [maximise] carbon benefits.”

It’s still early days, and both Margaret and Jenny are keen that the local community is at the heart of planning the future. “There’s a real feeling in the town that this could be a new chapter; a chance to bring in new energy, kickstart new enterprises”, says Jenny. “But what we don’t want is to project our vision on people”. Instead, she says, “we’ll be really open and transparent, create lots of opportunities for people to come and engage [with us], and then shape it from there. The community has to steer it, really co-create it.”

The change in ownership is now celebrated as part of the Common Riding, with specially composed tunes by a local piper – a source of particular pleasure for Margaret, decades after she was captivated by the event as a small girl on her summer holiday. “The town has been in limbo for many years. But this land coming into the community gives us a real sense of wellbeing again, you know? Because it’s ours. And it’s in our hands as to how it will develop.”

Published January 2023

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network