Meet the rewilders: Sussex Kelp Recovery Project

In Sussex, relentless campaigning by an eclectic group of individuals and organisations, now unified under the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project, has brought coastal kelp beds back from the brink — and paved the way for some joined-up thinking on marine rewilding.

Beneath the waves, beneath the radar

‘Out of sight, out of mind’. It’s a phrase which keeps coming up when people talk about the vast, rich beds of kelp that once lay along the Sussex shoreline. By their very nature, they’re largely invisible, just offshore, beneath the waves. As Sussex Wildlife Trust’s Henri Brocklebank (pictured above) puts it: “Many people weren’t even aware that the kelp was there — even when, suddenly, it wasn’t.”

Invisible, perhaps, but incredibly valuable. When kelp washes up on the beaches, it’s a limp, brown splodge. At home on the seabed, it’s a different story: a rich, waving array of plants, sometimes described as a ‘marine forest’ whose canopy is at the heart of one of the richest, most productive ecosystems in Britain, on or offshore. Kelp forests provide food and shelter for numerous fish, mammals and birds. A single plant can support a whole host of marine creatures.

The story so far

- What & how: A successful campaign to support an exclusion on near-shore bottom trawling, and a whole range of activities by experts, campaigners and interest groups to manage and monitor the coastal sea life as it recovers

- Where: Sussex coastal waters

- Future potential income: Improved catches for local fishing businesses; nature-based tourism

- Ecosystem benefits: Recovering wildlife and increased biodiversity; storm surge protection; potential carbon sequestration and storage

They’re fishermen’s friends, too: vital nurseries and foraging grounds for a whole range of commercially lucrative stock, from crabs and lobsters to cuttlefish, bass and sea bream. They also act as a buffer against storm surges and coastal erosion, and they could be a vital sink to soak up CO2.

So when it became clear in the late-teens that a shocking 96% of Sussex’s kelp beds had been wiped out since the 1980s, says Henri, “jaws just hit the floor”. She’s now leading the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project (SKRP), and was earlier a key figure in promoting the Help Our Kelp campaign, which successfully backed calls for a new local byelaw excluding bottom trawling from the areas where the kelp had once flourished.

Such a dramatic loss can’t be explained by fishing alone, though. Rather, it’s the result of an unfortunate — and for the kelp, deadly — coincidence. Dr Chris Yesson, a senior research fellow and seabed specialist at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), which is helping lead research into the kelp’s history and recovery, explains what happened. Kelp beds are sporadically broken up by storms, he says, and when the Great Storm of 1987 hit the Sussex shoreline, it did exactly that — albeit with particularly damaging effects, given its severity. Normally, the kelp would gradually recover. But with desperately bad timing, the aftermath of the storm coincided with a rapid expansion of bottom trawling in the area.

Usually, says Chris, trawlers avoid thick, established kelp beds, “because all the kelp gets tangled in your nets, and it’s a massive pain to get it out, and you don’t get a catch, basically.” But with the kelp beds only recently broken up, they didn’t have a chance to recover before the trawlers were in place. The result? With no kelp to impede their progress, the boats could drag their nets clean along the seabed, usually in pairs, with the weighted nets being towed between them. Wherever they passed, they ripped up virtually every living thing on the seabed, leaving a wasteland in its place.

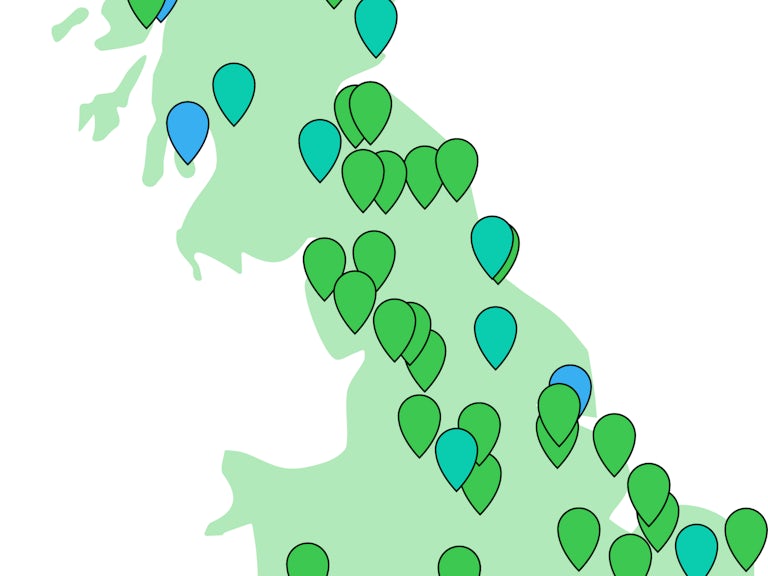

The Rewilding Network

The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project is part of our Rewilding Network , the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Raising the alarm

Beneath the waves, beneath the radar, maybe – but the impacts of wiping out the heart of a whole ecosystem were making themselves felt, nonetheless. Its destruction doesn’t just damage wildlife; it affects the local Sussex fishing boats too – most of which don’t practise bottom trawling. Catches were taking a hit. Partly as a result, says Henri, some fishers were giving up. Among them was Clive Mills, from Bognor. His family have lived and fished off this coast for generations – “My wife’s lot supplied lobsters to Charles the Second”, he says. But by the end of the 90s, he was facing a grim reality check. “I loved fishing, it’s in the blood — but I had no money. I had young kids and I had nothing.” For Clive, that meant reluctantly turning his back on the sea and starting a haulage business.

Yet for years, even while the effects were starting to bite, the extent of the kelp destruction went largely unseen. “Almost nobody realised it was missing”, says Henri. “People who lived right next to the beach didn’t notice it was gone.” A very few, though, spotted that things were amiss, she says, “and none more so than Eric”.

Talk to anyone involved in the Sussex kelp saga, and it’s not long before the name Eric Smith — one of the Sussex shoreline’s most indomitable characters — is on their lips. Now 75, Eric has spent his life free diving, ever since, as a boy, he fell in love with spear fishing. Sitting in a Shoreham pub with his daughter, also a keen diver, Eric recalls how he used to have to swim out a mile “just to get past the kelp”. By the early 2000s, he says, it was clear that things had changed. There was a lot less kelp, and fewer fish too. And he had no doubt as to the cause: trawling. “I had a dive one day in 2008, that was a real eye opener. I’d been in recently and it was beautiful – there were bream everywhere, pollock, bass, rays — you name it. But a couple of trawlers had gone through and everything got smashed to pieces. The bream had gone, the kelp, everything had gone.” He’s even seen white marks on the trawlers — a sign that they’d been stripping the seas right down to their chalky beds.

“The impacts of wiping out the heart of a whole ecosystem were making themselves felt. It affects the local fishing boats too.”

Incensed by the destruction in the waters he knew so well, Eric took action, writing letters and articles for fishery magazines about the destruction he was seeing on the seabed. But he also reached out to a body which, to most people, was as little known as the kelp itself: the Sussex Inshore Fisheries Conservation Authority

(IFCA). It’s one of 10 such IFCAs in the UK — statutory authorities charged with managing fisheries and the marine environment from the high water mark to six nautical miles offshore. Each has a governing committee drawn from Natural England, the Environment Agency, local councillors and stakeholders. Crucially, the IFCAs are allowed to write and enforce byelaws — subject to these being signed off by the Defra Secretary of State, and only following an extensive public consultation.

Eric’s evidence helped confirm what IFCA was already suspecting: that the declining fish stocks they’d been observing for some time was in large part due to the bottom trawling. “IFCA dug out a kelp survey from the 1980s commissioned by Worthing Council”, says Henri, and that showed just how much kelp had been lost since then. It was clear to IFCA that only a trawling exclusion could give the kelp a chance to recover, and so allow the fish stocks it supported to do so too. But that meant building enough stakeholder and public support for a new byelaw, which necessarily follows a statutory consultation process.

IFCA itself couldn’t campaign for this, explains its current Chief Fisheries and Conservation Officer, Rob Pearson: “We have to be strictly neutral”. It can only do its work by balancing the interests of different groups of fishermen, conservationists, scientists and so on: “As someone told me when I started this job, you’ll know you’re doing about right when everybody’s a little bit annoyed with you. If you’ve got one side really annoyed, and the other incredibly happy, then you probably haven’t balanced things quite right.”

David Attenborough — campaign gold

Others had no such constraints — not least wildlife filmmaker Sarah Cunliffe and her appropriately named Big Wave production company. Like Henri, Sarah had grown up in Sussex. She’d studied the wildlife off Selsey, and remembered the vast kelp forests which once thrived there. And like Henri, she had no idea that they’d vanished. “In 2019, I was having a coffee with Sean Ashworth [then Deputy Chief at IFCA], and moaning about how IFCA should do more about illegal shellfish collection… and he mentioned that he was working on a byelaw linked to the loss of the former kelp habitat… I was completely horrified when I realised that the kelp had essentially gone in my lifetime, on my watch – an entire habitat disappearing!”

“I said to Sean ‘No one will know what kelp is, let alone why they need to care about it’.” There and then, she resolved to make a film to raise public awareness of the IFCA consultation. She struck campaign gold when she persuaded Sir David Attenborough to narrate it . With the film in the bag, Sarah turned her attention to how best to bolster the case for the byelaw. She convened a meeting of representatives from the Sussex Wildlife Trust (SWT), the Blue Marine Foundation and Portsmouth University – as well as statutory authority IFCA.

That was when the fantastically catchy and tweetable campaign slogan ‘#HelpOurKelp’ first came into being, which was boosted enormously by the splash made by the film. Released just as the consultation period got under way, it immediately sparked coverage in local and national media. “It was trending online, it was on the BBC, it was seen by millions…. [The film] really did do what we set out to achieve, which was to put kelp on the map.”

With that momentum accelerating, a second meeting, this time also including the Marine Conservation Society, firmed up plans for the campaign; SWT took on a co-ordinating role, with Henri as its chair. Key to its success was the way it built on the enthusiasm generated by Sarah’s film, to win local support for the byelaw. “The reaction from the general public was just incredible”, recalls Sarah. “It felt like they were really excited at the possibility of doing something positive. It can feel so bleak out there, so just having the slightest inkling of positive news [was really motivating]”. Eric agrees: “People are craving good news. Really craving it.”

It was like no consultation IFCA had ever done before. “Normally there would be a handful of responses”, says Sarah. “Suddenly there were thousands!” From IFCA’s point of view, too, that was a result. Not only did they win the support they needed for the byelaw, says IFCA’s Rob Pearson, but “as a local regulator, we need engagement with our local stakeholders. And that’s not always easy to do. So when you get something like Help Our Kelp, which really gets the news out there, it’s massively beneficial.”

Interestingly, the enthusiasm was in stark contrast to some past attitudes to kelp, says Chris Yesson. “If you look at local newspapers from the 1950s on, you’ll see headlines like ‘The Scourge of Kelp is Back!’.” At the time, its vital role in the marine environment was barely understood; instead, locals worried that sporadic drifts of smelly seaweed washing onto the beaches might put off the tourists. “Forty years back, the local council saw it as a blight on the economy, and were considering dragging chains across the seabed to get rid of it. There was even a report that they were considering using explosives!”

It’s a tribute to the progress in marine and fisheries science, the shift in attitudes to the environment, and not least the brilliance of campaigners like Sarah and Henri, along with the charisma of Sir David, that there was barely a whiff of opposition to the ban from the public.

But what about those in the fishing industry? As Clive himself says, they are by nature suspicious of regulation, and some recoiled at being told what to do “by a bunch of idiots with degrees who know nothing about the sea”. But many were suffering from declining catches and, grudgingly or otherwise, accepted the need for some action.

So with massive public backing, it was no surprise when the Secretary of State duly did the necessary, and the Sussex Nearshore Trawling Byelaw came into force early in 2021.

A coalition for kelp

Anticipating the outcome, Henri and her colleagues at SWT had already been planning for the next step – how to maximise the conservation benefits that a ban would bring. “We were thinking ‘What does the world look like once we have a byelaw? What do we need to have ready? What relationships do we need to put in place?’ So we started quietly formulating some plans, gathering allies and putting in tentative funding bids.”

Cheered by the way conservation groups had been inspired by Sarah to come together under the Help Our Kelp umbrella, Henri was keen to keep the collaboration going. And so once the byelaw was passed, and funding secured, Help Our Kelp transformed into the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project, with another local filmmaker — and IFCA board member — Sally Ashby as its first coordinator.

Compared to rewilding projects on land, says Sally, ones in “marine areas, which are effectively a commons, are hugely complex — and expensive — to manage and monitor.”

That complexity hit home when, in her first week in the job, she convened a meeting of relevant stakeholders — and over 40 organisations turned up! To bring everything together, SWT convened on behalf of SKRP an expert Kelp Summit at the end of 2021. It featured a wide range of people who were part of the project, including experts like Dr Chris Yesson, and others from IFCA, universities including Sussex, Brighton and UCL, local authorities and campaign groups.

Since then, scientists have been gathering a huge amount of baseline data on the health (or otherwise) of the kelp and its associated ecosystem since the trawling exclusion. Among the work underway, Sussex IFCA — supported by ZSL and the Blue Marine Foundation — is doing video surveys, with a series of carefully planned transects using underwater cameras. University of Sussex researchers are monitoring just what species are present at the moment, using static cameras, acoustic surveys and sophisticated environmental DNA sampling techniques.

The Blue Marine Foundation and the University of Sussex are applying baited underwater video techniques to monitor fish recovery, and working with fishers from Selsey to study crab and lobster populations. The University of Brighton and Queen Mary’s University of London are exploring the extent to which the kelp might act as a carbon store. And using innovation funding from Rewilding Britain, the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project is leading stakeholder engagement to identify priority actions to reduce the impact of Sussex sediment in the water — from activities further upstream in the region’s waterways to other marine activities that could be impacting the kelp’s re-establishment.

Recovery takes root

So the million dollar question: now that trawling is out of the picture, is the kelp coming back? The short answer is yes — local divers, for example, are reporting new growths of kelp on wrecks offshore, and kelp is washing up on the beaches in quantities not seen in years — but it’s happening piecemeal, here and there, and evidence remains anecdotal. As well as areas where kelp seems to be making a tentative return, there are intertidal areas where it is still being lost.

And that’s to be expected, says ZSL’s Chris Yesson. “It’s a slow process – we have to have patience. It’s not a one-to-two year recovery — it’s more like five-to-ten.” Henri Brocklebank agrees: “Some people find it frustratingly slow, but I don’t. Let’s take a terrestrial comparison. Take a field that’s been under the plough for 40 years, and you suddenly stop ploughing it. You’re not going to end up with an ancient woodland overnight. These things take time. And we’ve only just left the seabed alone.”

Leaving kelp aside though, it’s the speed with which the wider seabed ecosystem is recovering that has surprised and delighted everyone involved. Mussel beds, which can act as a solid substrate for the kelp, are expanding, dolphins reappearing in huge pods, and, says Eric, fish that haven’t been seen for years, like electric rays, are back. Others, like stingrays are there in force — and so it goes on. The web of life is reweaving itself at a speed and scale that few dared anticipate. It’s a recovery that’s been gorgeously captured by Sarah Cunliffe in another film Our Sea Forest

, featuring Eric, which has been recently shown on the BBC.

“Take a field that’s been under the plough for 40 years, and you suddenly stop ploughing it. You’re not going to end up with an ancient woodland overnight. These things take time. And we’ve only just left the seabed alone.”

All this returning wildlife is good news for fishers too, says Clive. “There was a super pod of 100 or so dolphins off Brighton and Worthing just recently. Now, if dolphins are there in that number, there’s only one reason: they’re here to feed. And if they’re here to feed, that means there’s a good fish stock. It means the shoals aren’t getting broken up by the trawls.”

After years in the haulage business, Clive has even been inspired to take up fishing again. Along with three friends, he’s injected new life into the Bognor Fishermen’s Association, transforming a derelict shed on the town beach into a fish stall, selling the day’s catch to local residents. Blue Marine Foundation tells his heartwarming story in Bognor Fishing – Back from the Brink .

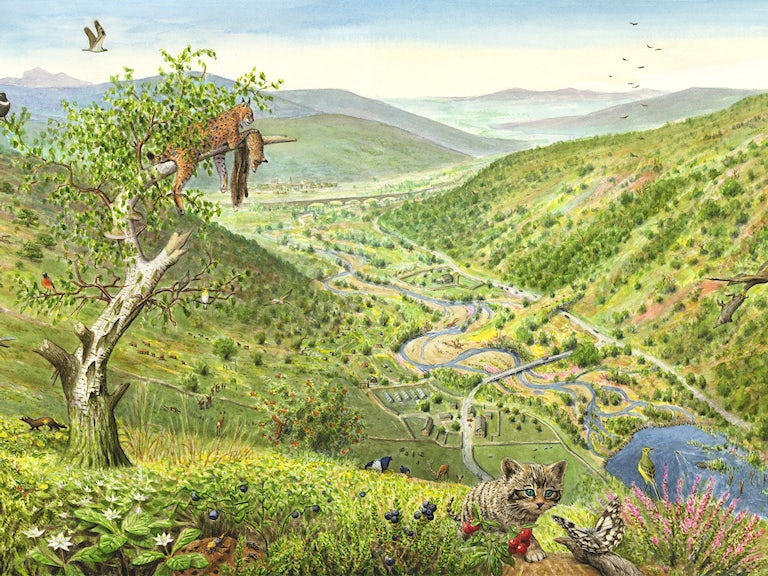

Big picture thinking

What’s really good news for kelp and the wider marine ecosystem off the Sussex coast is that several innovative new rewilding initiatives have now launched in the area, with a big picture vision for land and sea. Local farmer James Baird has co-founded Weald to Waves , a wildlife corridor from the recovering kelp all the way to Ashdown Forest, via the Knepp Wildland. One sure benefit for kelp will be a reduction in the pollution and run-off that impedes its growth. And Sussex Bay , a collaboration of over 200 groups, organisations, and partners, aims to create and deliver a pioneering seascape-scale vision for 100 miles of coastline from Selsey Bill to Camber Sands.

“The landmark work of Sussex IFCA has inspired so many people and organisations. The level of engagement we’ve had from different sectors is quite extraordinary”, says Henri. The scale and the speed with which it’s taken shape is “above and beyond any project I’ve worked on in my career”, she adds. “We’re all learning, all the time, because nothing like this has ever been done before.”

Published June 2024

Seascape scale vision

Sussex Bay was awarded £100k through our Rewilding Challenge Fund, an annual fund granted to the rewilding project which shows the maximum potential to work with others to scale up rewilding.

Find out more

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network