Meet the rewilders: Wild Ken Hill

Inspired by the achievements of proto-rewilders Knepp in Sussex, Dominic Buscall abandoned a career in management consultancy to lead a transformation of his family’s Norfolk farm – helping take rewilding to prime time TV.

When fire raced through a stretch of Norfolk coastal scrub in the scorching summer of 2022, it triggered an outpouring of public concern. Because this wasn’t just any heatwave blaze: it had struck a landscape made famous by one of the nation’s favourite TV programmes – Springwatch.

Within hours, the owners of Wild Ken Hill were fielding messages of sympathy – and even offers of donations – from people who’d been touched by its story. Some were surprised to be told that, no, it wasn’t a charity, but rather a commercial farm.

The land at Ken Hill has been worked by the same family for over 150 years, but is now undergoing something of a revolution, mixing regenerative agriculture with traditional conservation and some far-from-traditional rewilding. And, thanks to Springwatch and its sister programmes, doing so under something of a spotlight.

The story so far

- Who: Dominic Buscall, Founder

- Where & when: Wild Ken Hill, Norfolk, 2019 onwards

- What: Rewilding ex-arable fields and woodland, nature conservation, regenerative farming

- How: Farming and contracting income and subsidies; eco-tourism and environmental grants

- Income – current: Farming and contracting income and subsidies; eco-tourism and environmental grants

- Income – future potential: Public and private environmental markets

- Ecosystem benefits: Nature recovery on ex-arable and grazing land; revival of local wildlife species; improved overall biodiversity and soil health

At its heart is Dominic Buscall, an energetic young man with long coppery hair, who at little more than 30 is leading the transformation of the land farmed by his father and several generations before him. Speaking to him, it’s clear that the environmental crisis is something that has been weighing on his mind for some time. As a teenager, he recalls, “I was already quite appalled by climate change”. But by following his academic interests at university, where he studied history, he felt he’d ruled himself “out of any meaningful career” in the subject. “I thought the response to the crisis would be driven by technology: you know, electric cars, renewable energy and so on.” Hence a job for engineers, or physicists, rather than a humanities graduate.

Instead, he threw himself into the pressure-cooker world of management consultancy, working till 3 a.m. in locations ranging from Sydney and Mumbai to Derby and Slough (“it’s not all glamorous”, he laughs). The pace of work was “shattering” though, and in 2018 he took a breather in the form of a six-month sabbatical. It was a chance to reflect not only on his future, but that of the land on which he’d been raised.

Together with his father, Dominic took a long hard look at both the economics of the 1,600-hectare farm, and its environmental impact too. Economically, it wasn’t doing badly. “We’re lucky in that at least some of the farm is on relatively good soils, plus we did contracting for five other farms locally, so that scale helped keep overall costs per hectare down.” But there was always the risk of bad weather, he adds, and “if you stripped out the support payments we had from the [EU’s] Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), we were making a loss one year in five. That’s better than some, of course, but it’s just not good business sense.”

Meanwhile, post-Brexit, the government had signalled that the area-based CAP-style payments would cease, to be replaced by some form of subsidy for ‘public goods’ – notably environmental protection. Put all that together, and the business case for shifting to a different kind of model was pretty compelling. That case was strengthened for Dominic by meeting Knepp’s Charlie Burrell and Rewilding Britain’s Alastair Driver, when they came to talk to Norfolk land managers. “It helped me understand how rewilding could be applied in England. I realised that it presented both an opportunity to future proof the financial sustainability of the farm, and fulfil my desire to do something about biodiversity and climate change.”

It helped, too, that Dominic’s father, who was still in overall charge of the business, had come round to a similar point of view. They agreed that “private land managers own the majority of the UK, and they farm the majority of the UK, and that’s where change needs to happen”, he says. “So we agreed, let’s create an environmental exemplar. And within four months, we had a scheme up and running!”

Dominic went back to his day (and half the night) job post-sabbatical, but his heart was no longer in it, and he soon gave it up to focus on the transformation of Ken Hill. It would be easy to see his time in consultancy as a cul-de-sac, but he insists the experience wasn’t wasted. “It taught me how to get stuff done and manage projects to tight deadlines. Although I’m all too aware that I haven’t got agricultural or ecological training, so there’s definitely a degree of imposter syndrome! But I’ve come to realise that the climate and nature crises need a mix of interdisciplinary skills – it can’t all just be done by ecologists.”

DIFFERENT STROKES FOR DIFFERENT HABITATS

No matter what skillset is in play, transforming a conventional arable farm into a haven for nature in short order is no small ask. Yet they weren’t entirely starting from scratch. “There’s a lot of talk about how 30% of land should be dedicated to biodiversity”, notes Dominic. “Well, we were already at 25%. We had longstanding grazing marsh [by the sea], we had some woodland, pretty good field margins, and we hadn’t used insecticides for seven or eight years”.

When it came to a radical reappraisal of the potential for nature recovery, though, it soon became clear to Dominic and his team that it would be far from a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Instead, it called for essentially three strategies, corresponding to its three broad swathes of habitat.

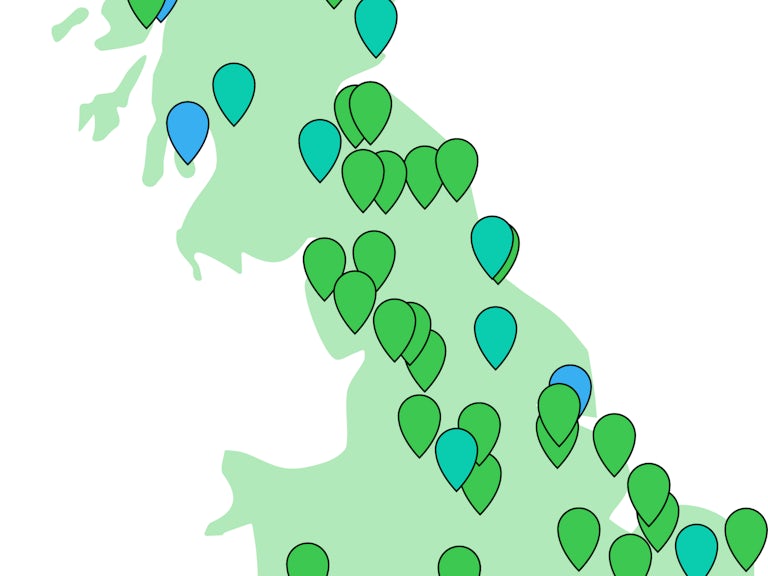

The Rewilding Network

Wild Ken Hill is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

First up, the coastal marshlands – where the wildfire would sweep through – where they took what he describes as a “traditional nature conservation approach, [involving] a series of major interventions to support target species”, notably wading birds like the avocet and curlew. That meant some “significant earthworks” to raise the water level, along with scrub clearance and carefully managed grazing. “It’s the sort of very outcome-focused, high cost per hectare intervention which you’d find on most nature reserves.”

Then there’s the higher ground, accounting for a little over half the land, where good soils have encouraged the Buscalls to carry on farming – but with the emphasis on a regenerative approach. Which sounds nuanced, but as Dominic explains, “it’s actually a whole system rethink”. The focus here is on restoring soil health: so out go the plough and chemical fertilisers and pesticides, and in comes ‘no-till’ farming, using cover crops to safeguard the soil after each harvest, and nitrogen-fixing plants to boost fertility. People who’ve been working the farm for decades have had to learn a whole new set of skills, he says. “We’ve done three years, and we’ve got at least four to go before we’re where we want to be. It’s a proper, big piece of work; a proper journey.”

But it’s the area in-between, a 400-hectare mix of ex-arable fields and woodland, where true rewilding is getting going. The decision to take this piece of landout of agriculture completely was relatively easy: its poor soils produced meagre returns. Ironically, while this is where the most revolutionary changes are underway, active interventions are relatively minimal. It’s more a case of not doing stuff, says Dominic. “Natural regeneration is going to happen without your help. You don’t need to plant trees, you don’t need to sow seed.”

Much of the early activity actually happened in the office, rather than the fields: organising scientific research programmes to make baseline studies and monitor changes, and getting funding applications under way, notably for the creation of wood pasture under the Countryside Stewardship scheme.

PIGS, PONIES AND PRECEDENTS

When it did come to interventions on the ground, he adds, there was a “fabulous pioneering precedent” in Knepp. “I could read Isabella’s Tree’s book [Wilding, her celebrated account of Knepp’s transition] and think, ‘Yup, that’s going to work, and… that’s going to work.’ I really didn’t need to reinvent the wheel. It’s the consulting mindset coming out. We’d have called it ‘leveraging external material’ or something like that. Copying, basically!”

One of the precedents was the introduction of ‘natural grazers’ to help break up and fertilise the soil, browse off vegetation and reinvigorate a variety of plant growth. In this case, 45 Red Poll cattle – descendants of a traditional Norfolk breed – along with 20 Exmoor ponies and a clutch of Tamworth pigs. They’ve been joined by a family of beavers, the first to be reintroduced into Norfolk, which have already started to breed.

Walking round the rewilding zone, you can already see change under way. Ponies graze and scamper beside dusty tracks, huge hairy brown Tamworths shelter in the woodland edge, and the old arable fields are starting to sprout shrubs and saplings, along inevitably with a sea of ragwort – a familiar appearance in the early stages of rewilding. This can cause consternation because of its potential toxicity to livestock, but here again, Dominic takes comfort from Knepp. “I know I don’t have to worry about it, because we’ve seen what happened there”, where the ragwort faded as the process of ecological succession unfolded.

The pace of that succession at Wild Ken Hill became clear with the results of a painstaking plant survey, released early in 2023. This showed that, compared to a 2019 baseline, the average number of plants in sampled plots in the rewilding area had doubled. Even higher increases were observed in the ex-arable fields, where they’d more than quadrupled now nature was taking its course.

There’s been good news, too, on the climate front. A study mixing physical soil samples with sophisticated modelling suggests that, across all its landholdings, Wild Ken Hill is emitting around 800 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (t CO2 e). But it’s now sequestering five times as much (around 4,000 tonnes CO2 e) – making it definitively ‘carbon positive’.

So what do other farmers and locals make of it all? That’s where being able to cite Knepp’s experience is a huge help, particularly when it comes to persuading landowners of the merits of rewilding, says Dominic. “Knepp’s won so many arguments, made so many good points, that the heat’s been taken out of the debate for people like us. We can just swim in their slipstream.”

And unlike Knepp in its early days, there’s been little outright opposition among other farmers. Some are “curious, even sceptical: they want to come and have a look, ask some good questions – quite difficult ones, sometimes!” It helps that the Buscalls are long-established, trusted farmers in the area, of course, but they’re not, to coin an inappropriate metaphor, ploughing a lonely furrow. “There are other projects popping up in Norfolk, so there is actually quite a strong community of land managers like us who think this is a really sensible way to go.”

THE SPRINGWATCH EFFECT

Once the transition was under way, Ken Hill became Wild Ken Hill, to signal its new identity. The name change has sparked the odd amusing confusion. “People ask, ‘So who was Ken Hill and what made him wild?!” Dominic agrees that it conjures up an image of a swaggering Texan in a ten-gallon hat… But there’s no going back, because the name is now celebrated thanks to Springwatch, whose presenters, including the iconic Chris Packham, based themselves at Wild Ken Hill for several series.

“A researcher at the BBC read a little think piece I’d done for our website”, Dominic recalls, adding that after “I’d done a bit of a sales pitch, they came up and had a look, and decided to start filming here.” Any fears that having a TV crew complete with celeb presenters wandering around could be disruptive proved unfounded. “They’ve been really easy to work with; very respectful. And I’m very proud of the way they’ve told the story. I think it’s quite a big deal to have words like rewilding and regenerative farming, jargony terms from conservation, mentioned repeatedly to millions of people on prime time TV”.

“It’s quite a big deal to have words like rewilding and regenerative farming mentioned repeatedly to millions of people on prime time TV.”

The fame has undoubtedly helped draw visitors to the site – just as well, since rewilding experience tours and workshops are part of the business model – and boosted support locally as well. That helps smooth over the odd hackle raised, for example, by the need to divert a footpath, which had upset some dog-walking locals. More broadly, though, the issue of public access versus nature protection remains a live one for Dominic.

“It’s a difficult tightrope to walk. On the one hand, we’re committed to restoring nature, and therefore we have to respect the integrity of it. And on the other, we’re also committed to engaging people about nature. They need to have access to it if they’re going to understand and respect it. But unfettered access to our high value nature areas can be very disruptive. And we have plenty of evidence of that – not least the fire: we don’t know how it started, but it was almost certainly indirectly because of the presence of people, whether it’s barbecues, or cigarettes, or glass – any of the above [could have sparked the flames].” Getting the balance right “is a real challenge for [projects such as ours]”, he says.

But, he adds, “one of the criticisms of rewilding is that it involves removing people from a landscape, and I absolutely, vehemently deny that. We’ve created more jobs, more volunteering opportunities, we have more school visits, more open days, we’re more connected with our community than ever before.”

“One of the things about [working in] the environmental sector”, says Dominic at the end of our conversation, “is that the more you get into it, and the more you learn, the less optimistic you can become, [because] you’re so aware of all the problems out there. But then I come back to Ken Hill, and I know I’m with good people doing good things to help address it. And that’s really good for the soul. I know that this land can be a refuge, and a place of hope.”

Published July 2023

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network