What does rewilding look like?

We imagine how rewilding can transform a degraded upland landscape.

Imagine life bursting back to our land and seas, where wildlife numbers are growing instead of shrinking and we’re working with nature, as a part of nature, instead of exploiting it. Nature can recover when given a chance. We have to give it that chance.

Watch the video below to see the transformation of an ecologically degraded part of Britain’s uplands…

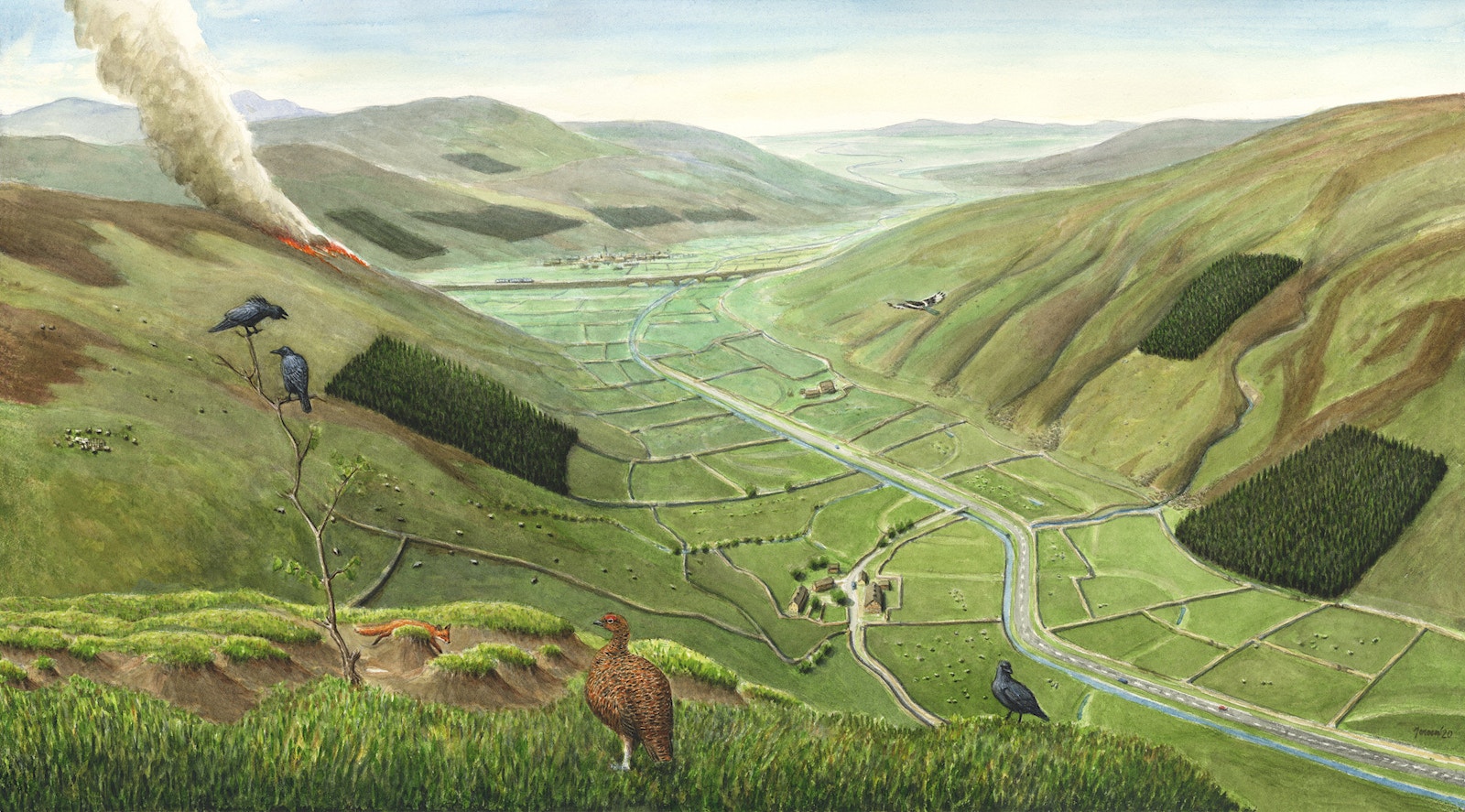

1. Present day: nature in distress

Once home to native woodlands, wetlands and meadows, many of our upland areas have lost huge swathes of their native wildlife over centuries. We have so much to gain by rewilding degraded land — increased carbon storage, flood mitigation, richer soils, flourishing wildlife and healthier, more beautiful places for people to live, work and play.

So what’s the story?

What can you see?

Or perhaps that should read, what can’t you see? Britain’s native trees and plants are mostly missing in this picture, which is typical of many upland areas. There’s very little wildlife overall, and not many people.

Human activity appears to be largely restricted to sheep farming, grouse shooting, and commercial forestry. People may come to stay and walk here in the ‘great outdoors’ but they won’t see much wildlife. Options for young people to earn a living are likely to be limited.

There’s a town on the railway line off in the distance. Is it thriving or struggling…?

Heather and eroding peat dominate the slopes on the left. Peat hags — degraded by historic acid rain, sheep grazing and repeated burning — are in the foreground of the picture. Moorland burning is continuing in the distance.

Trees are largely confined to regimented blocks of non-native conifers with little or no connection to their surroundings. Tiny fragments of broadleaved trees have managed to hang on, including the fledgling birch in the foreground of the picture and a thin ribbon lining the bottom of the stream flowing down to the valley floor.

Sheep have over-grazed the hills in much of this landscape. The ground is compacted through centuries of trampling. This is causing bad erosion and landslips, and contributes to the flood risk already exacerbated by the lack of vegetation.

Altered rivers and flood risk

The river is unnaturally straight. Like so many rivers in Britain, it has been straightened, widened and deepened. In some places, it has been separated from its floodplain by embankments. You can see the faint outlines of its original meandering course in the fields, the river’s floodplain. Some water is settling there.

During heavy rains most of the rain that falls in this catchment will rush off these billiard table hills and hurtle down this channel, increasing flood risk downstream.

There are no longer any trees or plants beside this river, which is a shame because falling timber can help slow the flow of water. This loss of riparian ecosystem diminishes biodiversity (leaf litter in rivers provides nutrients for amphibian life, for example).

We all like to get around with ease but modern roads have divided and fragmented habitats for wildlife, contributed pollution and made it more difficult for wildlife to move around. The road here is following the path of the river. In the past, an older track or highway would have been built to the side of the original meander.

Cash crop forestry

These dark angular swatches of trees are dense blocks of conifers grown for timber. Although forestry is slowly changing, they’re still often comprised of Sitka spruce, a fast-growing tree that’s native to Alaska. The conifers are usually planted close together in rows. They’re not representative of how our airy, mixed native woodlands would have grown and evolved after the Ice Age.

Forestry for timber is an important land use in Britain. We currently import vast amounts of timber, putting pressure on virgin forests around the world and helping to fuel illegal logging.

In Scotland, commercial conifer plantations account for 75% of the country’s tree cover (around 18% of Scotland’s land mass). In England, they account for 25% of the country’s tree cover (currently 10% of the land mass). The remaining trees are broadleaved – oak, rowan, ash and so on – Britain’s dominant native tree type.

We need to find ways to balance the demands of producing timber and expanding our natural, biodiverse, carbon-rich rainforests and woodlands.

Management for sport shooting

A grouse moor has been created on the left of the picture, probably sometime in the mid 19th century. If you squint, you might be able to see a couple of stone grouse butts where shooters stand to take aim at the grouse startled into flight by people beating the heather (grouse beaters).

The moor is on fire. Burning heather on grouse moors is a standard practice. It encourages the growth of new young shoots of heather, which grouse love. But this scorching eliminates the growth of other vegetation and wildlife, including trees and invertebrates that are unable to escape the flames in time.

Grouse moors are good for red grouse (that’s a red grouse in the forefront of the picture) and invertebrate species that are specific to heather. They are also attractive to some other ground nesting birds. But they’re intensively managed landscapes that suppress a wider, richer mix of plant and animal species.

Ironically, one of the species that grouse moors suppress is…the black grouse. Black grouse is the fastest declining bird species in the UK (says the RSPB). It likes to mingle in a mosaic of habitats, at the edge of forest and woodland – sometimes in the trees, sometimes out of the trees.

Red grouse, on the other hand, are happy in open heather-dominated landscapes. The beautiful black grouse, so fun and spectacular when it’s lecking, could be following the capercaillie to extinction.

Sheep — shaper of culture and land

Sheep are the dominant animal in this scene. There are over 15 million sheep in England, more than 10 million in Wales and nearly 7 million in Scotland. According to the National Sheep Association, the sector employs 34,000 people on farms and a further 111,405 jobs in allied industries. Sheep herding has been subsidised in the last few decades by the EU’s Common Agriculture Policy.

Sheep are believed to have first come to Britain around 4,000 BC, then in greater numbers during the Bronze Age as woodland diminished. It’s thought that there was only one type of sheep, the Soay or similar, until the Romans introduced different breeds.

Ecologically, the large scale intensive grazing of millions of mouths over centuries has shaped many of our upland and lowland areas, suppressing the growth of trees and other vegetation. This has dramatically reduced biodiversity.

The monoculture, billiard-table character of the intensively sheep-grazed areas attract generalist species, which are easily able to adapt and even thrive in these conditions. The picture shows a typical mix of these species: red fox (often disliked and persecuted by farmers because they kill young lambs), carrion crow and magpie.

Regeneration potential

The conifer plantations show that trees and vegetation can take root and grow on these impoverished upland hills. But any attempts at reforesting will likely depend on tree planting because there is such little seed source, and what seed sources there are will likely be limited to very few species.

In addition, the dominant thick swards of grass make it a challenge for seeds to get the light they need to start growing. Restoring the uplands needs to address these sorts of ecological challenges, as well as cultural and social ones.

What wildlife can you spot?

Mammals

Red fox (vulpes vulpes), sheep (ovis aries)

Birds

Red grouse (Lagopus lagopus scotica), carrion crow (corvus corone)

Trees and vegetation

Birch (betula), heather (Calluna vulgaris)

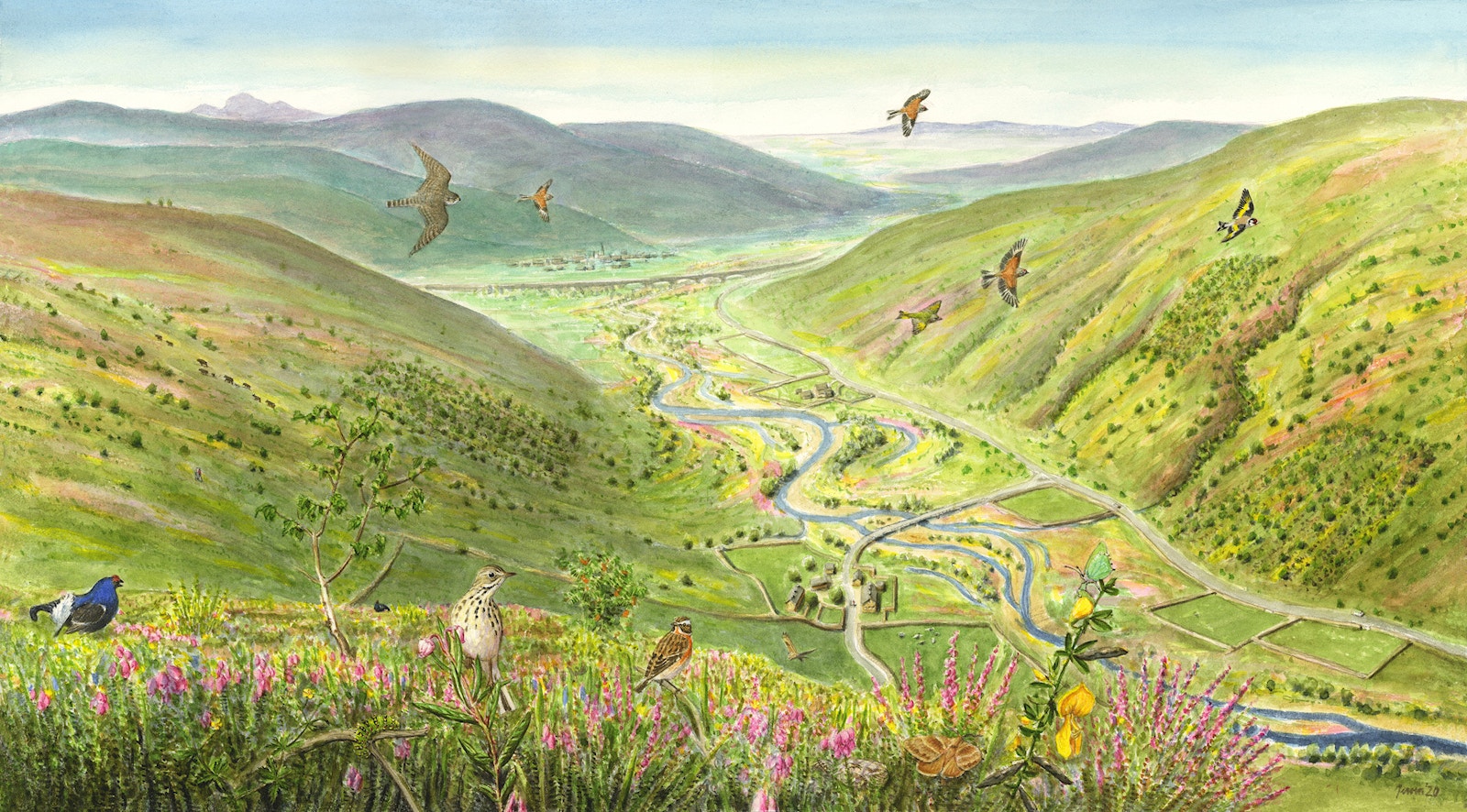

2. Into the future: nature starts to heal

If we made just a few changes, here’s what we could see.

What can you see?

Nature is recovering! Thanks to significantly reduced grazing pressure, seedlings can grow and the ground is less compacted. Fewer chemicals, fertilisers and animal medications are entering the soil and water. Reducing stocking numbers is not only beneficial to wildlife but can help farmers be profitable – see how upland farmer Chris Clark realised this on his farm in the Yorkshire Dales.

A few native breed cattle are grazing the slopes on the left. Descended from the ancient aurochs, these can play an important role in creating space in the landscape for seeds to grow through trampling vegetation and grazing.

Grazing animals play an important role in functioning ecosystems. Their browsing of trees and shrubs, through breaking off branches and twigs, encourages new shoots. Their horns debark trees and their dung fertilises the land, and provides habitat for many types of dung beetle and other invertebrates (read The role of grazers and browsers)

Bringing back the broadleaves

The forestry blocks have been felled and planted with native deciduous trees. The new trees will likely need protection from deer by tree guards or fences, but within five to ten years these can be removed. As the trees start to take hold, they’ll provide a seed source for natural regeneration in the future.

There’s a thicker ribbon of trees growing in the gullies thanks to the old trees hanging on in those steep areas less accessible for sheep grazing. These are providing an initial seed source for natural regeneration.

Trees absorb great quantities of rainfall through their roots system, while their leaf canopies slow the fall of rain. Without trees, water will run off these hills at speed and exacerbate flooding.

Restoring blanket bog (peat)

The peatland is starting to flourish following a restoration programme. The bare peat has revegetated and you can see heather, cross-leaved heath, bog rosemary, tormentil and Scotch broom. Can you spot the reclusive nightjar in the midst of it all?

This vegetation is supporting a fantastic variety of insects including moths and butterflies, as well as birds — all good food for raptors, such as the short-eared owl and merlin in the picture.

The slower flow of water off the hills is enabling the peat bog areas to become much lusher and wetter, with ferns and mosses, especially Sphagnum, now thriving. The risk of fire away from picnic areas and roadsides is now really low. Burning for grouse moor management has ceased altogether.

In the distance, you can see that sheep are primarily grazing now on the valley floor.

Wilder river and hills

New trees growing on the hills are helping to heal the erosion. The landslips have revegetated and the riverside road has been re-engineered to follow its original route.

Slowing the flow — that’s how to reduce flood risk. A meandering river slows the flow of water. Here, the embankments have been removed to allow the river to re-meander to its old course and reconnect with its floodplain.

Trees and plants are growing on this wetter ground, making the most of the nutrients washing into the soils as the river nourishes the land. Fallen trees and branches, as well as stones and boulders, also slow the flow of water in natural, wild rivers.

What wildlife can you spot?

Birds

Black grouse (Tetrao tetrix), goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis), greenfinch (Chloris chloris), linnet (Linaria cannabina), meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis), merlin (Falco columbarius), nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), short-eared owl (Asio flammeus), whinchat (Saxicola rubetra)

Insects

Emperor moth caterpillar (Saturnia pavonia), fox moth (hecla betulae), green hairstreak (Callophrys rubi)

Trees and vegetation

Birch (betula), rowan (Sorbus aucuparia), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), heather (Calluna vulgaris), cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix), bog rosemary (Andromeda polifolia), tormentil (Potentilla erecta), Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius)

3. Vision for tomorrow: a rewilded landscape

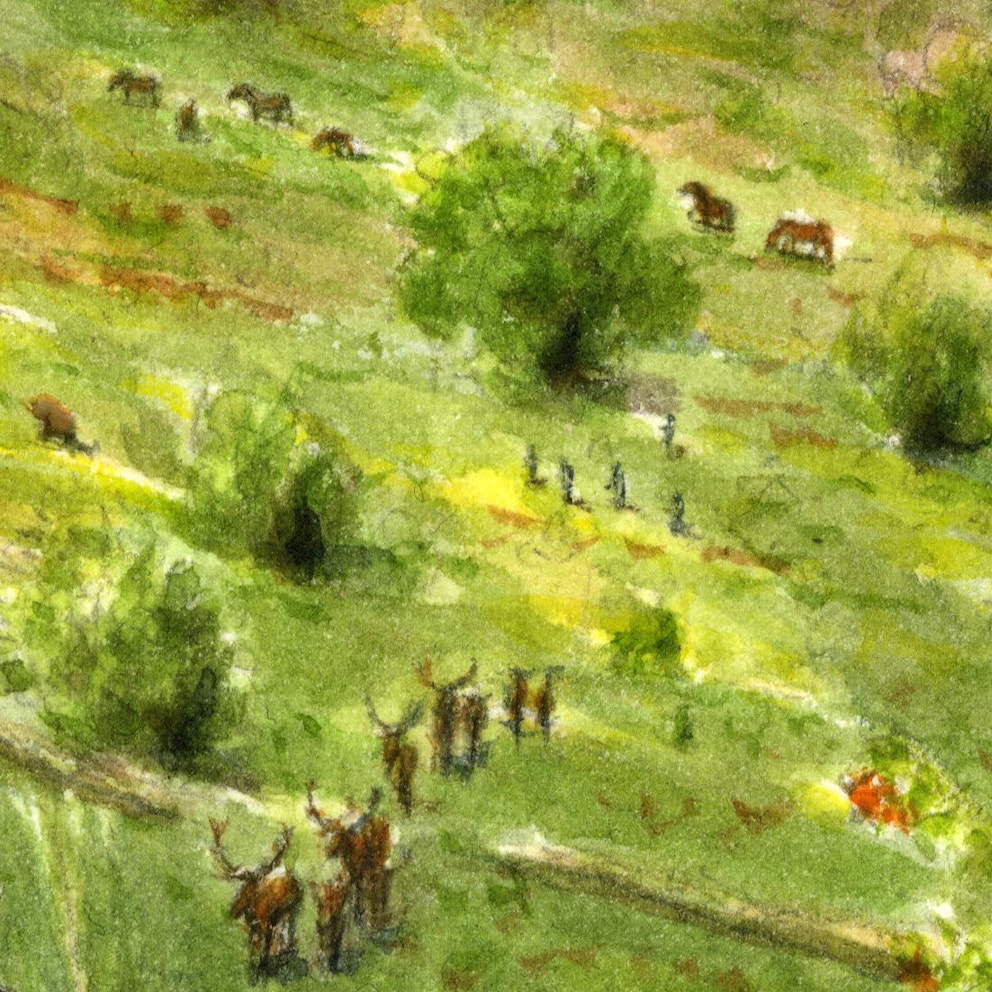

In 50 years, what might we see?

What might you see?

In 50 years, what might we see? There’s so much happening in this future scene. It’s a landscape full of life (including people), which is colourful, vibrant and echoing with birdsong.

Complexity and diversity is vital for strong, resilient, healthy ecosystems. Here we have people, birds, insects, fish, domesticated animals, wild grazers and predators all integrated and interacting among woodlands, wetlands and grasslands.

This is a true vision for rewilding. A flourishing of the living world with all the infinite connections and relationships that weave the unfathomably complex and magical web of life.

It’s a web of life of which we’re part and in which we can thrive.

Alive with people

-

Some day visitors are here to spot a beaver if they can © Jeroen Helmer -

A stalking party passes by berry pickers © Jeroen Helmer -

A cyclist arrives at the camping and glamping site © Jeroen Helmer -

Hikers share the hill with deer, ponies and highland cattle © Jeroen Helmer

Regenerative land use supports the earth, our health and provides opportunities for different livelihoods.

We can see people walking, stalking, foraging, cycling, camping, glamping, watching wildlife (see the hide next to the beaver pond), growing food. They’re still driving, keeping some sheep, travelling to the distant town. Perhaps there are artists, photographers, meditators, horse riders in the midst of the trees or up the hills. Perhaps canoeists and wild swimmers exploring the wild river and wetlands.

We estimate there could be as many as 50% more direct jobs through the rewilding of degraded land — for example, in wildlife monitoring, low impact silviculture, craft work, nature tourism, local food and drink products and high quality livestock products (read our recent report on this).

Our five principles of rewilding brings together the importance of people, scale and long-term thinking to the success of rewilding.

- Engage people and communities to ensure maximum benefits for the many

- Let nature lead and minimise interventions

- Look to create opportunities for resilient new nature-based economies

- Work at nature’s scale to rewild whole systems and not just fragments, ensuring nature is connected (so that species can move and adapt) and enabling peak potential for carbon sequestration.

- Ensure that your rewilding project is for the long-term, for the benefit of future generations.

Growing food sustainably

We can still grow food and have wild places! Sustainable agriculture works with nature and can incorporate livestock keeping, harvesting natural products, low impact crops, fishing and hunting. It means growing food within the capacity of the land and limiting extraction from our rivers and seas. It means acting with care for the health and wellbeing of future generations.

Here we see the use of polytunnels, beside the glamping and camping site, to grow local food, which might be sold from one of the nearby buildings.

There’s also a small orchard on the right, which might be growing some traditional apple and pear varieties.

The shop might offer eggs, venison, lamb and limited amounts of pasture-fed beef along with seasonal berries, apples and pears. We wouldn’t be surprised to find a few jars of local honey, cowberry jam ( known as lingonberry jelly when it comes from Sweden), a bottle of locally produced gin, flavoured with local fruits and herbs, and perhaps some homemade apple juice or cider.

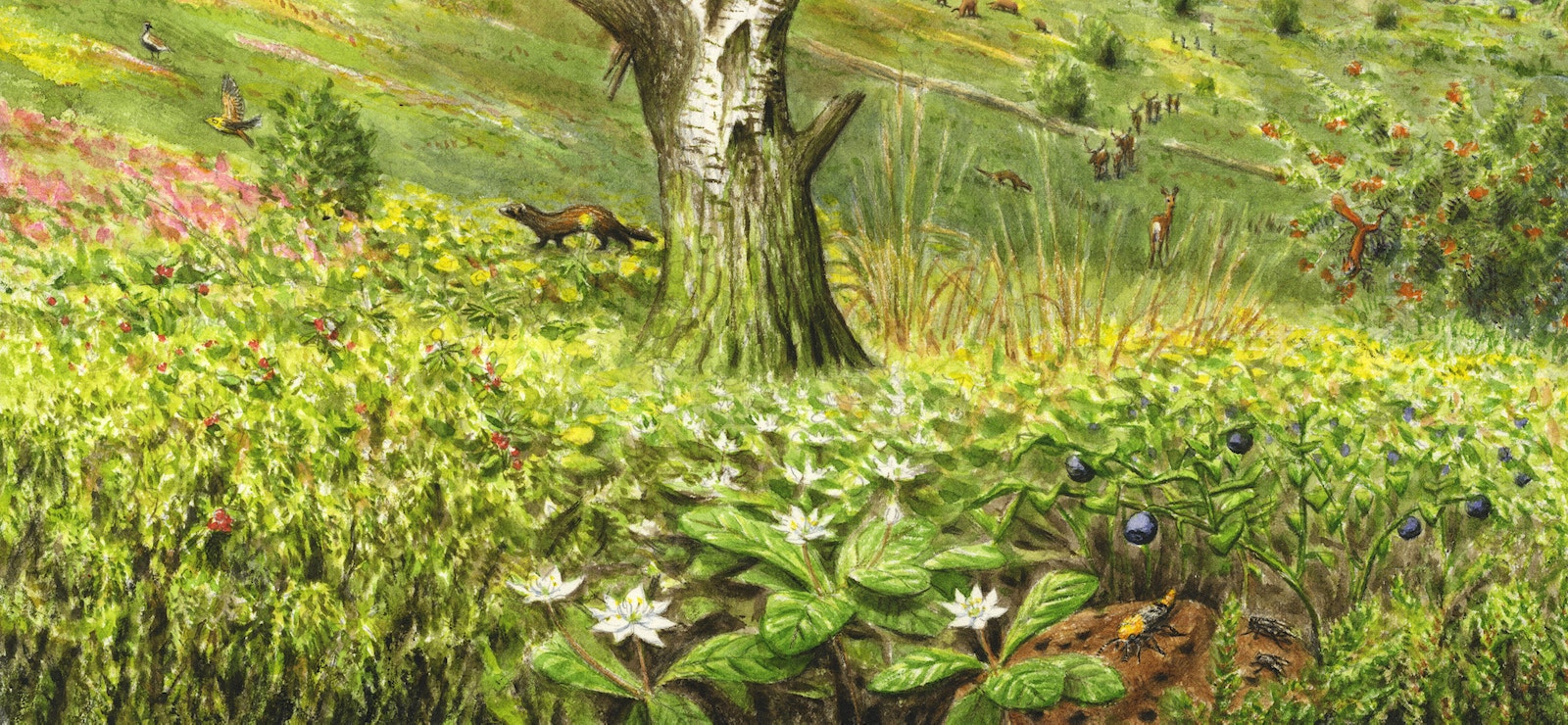

Food for foraging and fertilising

A lush understory of cowberry, chickweed wintergreen, bilberry and crowberry has now replaced the degraded peat. The berries are providing sweet treats for people, birds, larger herbivores such as deer and cattle, and smaller rodents such as voles. Perhaps that’s why the red and roe deer in the distance are heading in this direction.

That’s a polecat to the left of the tree, and an otter to the right in the distance. They’re likely foraging for small birds, frogs and birds’ eggs. Red squirrels are back in the area, following a translocation programme that brought them from Perthshire in Scotland back to their natural range across England. The recovery of the native woodlands and the return of pine martens, which predate grey squirrels, has made this possible.

Watch your step! That’s cattle dung in the foreground of the picture. Dung fertilises the ground and provides a home and sustenance for beetles such as the unusual Emus hirtus rove beetle here in the picture. Emus hirtus is found in continental Europe, and the south east of England at the moment.

As climate change brings warmer temperatures, the range of beetles, insects and many other animals will likely drift northwards. This is already happening for many species.

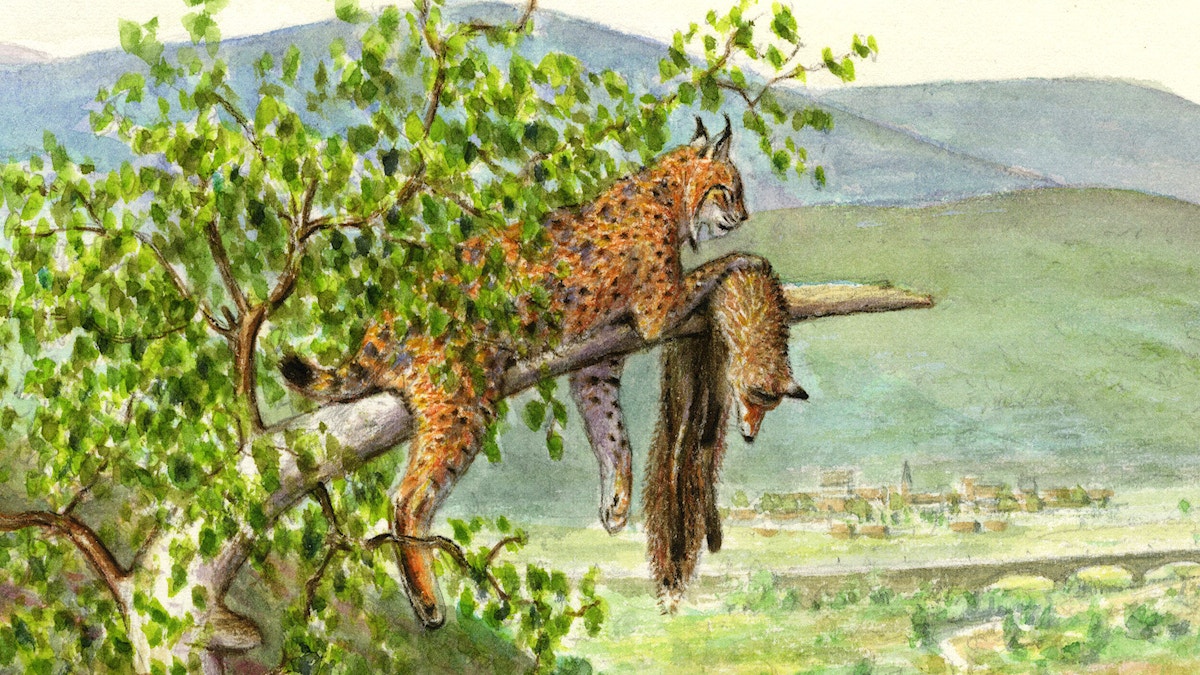

The lynx returns

The lynx is back! Following an in-depth consultation with the public and local stakeholders, and thanks to the ongoing restoration of their habitat, the lynx has been reintroduced.

These are shy, solitary creatures, happiest when ambush hunting and staying out of sight of prying human eyes. That doesn’t mean a more confident feline might not lazily survey the scene before it from the high vantage point of a mature tree branch. Despite their elusiveness, their presence is drawing visitors to the area.

The lynx’s favourite prey is roe deer and there’s plenty in the uplands to keep it happy. They’ll also go after foxes and other tasty mammals such as hares, squirrels, grouse, wild boar and red deer.

The carnivore herbivore balance

In addition to the lynx, the wildcat is recovering from the brink in this imagined future and is moving back into its home range across Britain.

The presence of the lynx and wildcat is enabling some predator/prey dynamics to shape the landscape. Natural processes such as these enable functioning food webs, which support a wide variety and abundance of species.

Mixed grazing and browsing from cattle, ponies, roe and red deer, wild boar and beaver is helping to create different types of open space across this landscape as the woodland expands and regenerates.

Freedom to roam

Wildlife is moving around without becoming roadkill, thanks to the newly built wildlife bridge. These bridges connect up important habitat, and enable animals to roam safely and freely across the road.

The golden eagle in the picture below is enjoying an increase in the availability of prey, such as wild boar. In the near future, perhaps golden eagles and other raptors across Britain will enjoy lives that are free from shootings, poisoning and other forms of persecution. Raptor persecution is illegal today but still persists in our countryside.

Restoring wetlands

You can see the re-naturalised river has blossomed into a thriving wetland complete with a family of beavers and a stunning dam that they’ve built.

The rich riparian ecosystem that’s evolving along the valley floor includes stands of dead trees and mixed vegetation, which is supporting a rich range of aquatic life including salmon and otters. There’s a family of wild boar rootling and foraging by the water in the bottom right of the picture, and a family of humans making their way to a wildlife hide by the water’s edge.

What wildlife can you spot?

Mammals

Beaver (Castor fiber), Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), Highland cow (Bos taurus taurus), otter (Lutra lutra), polecat (Mustela putorius), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), sheep (Ovis aries), wild boar (Sus scrofa), wild cat (Felis silvestris), wild horse (Equus ferus)

Insects

House fly (Polietes Lardarius), rove beetle (Emus hirtus), marbled white butterfly (Melanargia galathea)

Trees and vegetation

Birch (Betula), birch polypore bracket fungus (Fomitopsis betulina), rowan (Sorbus aucuparia), cowberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), chickweed wintergreen (Trientalis europaea), Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum)

Birds

Black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix), curlew (Numenius arquata), golden plover (Pluvialis apricaria), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), hen harrier (Circus cyaneus), magpie (Pica pica), osprey (Pandion haliaetus), redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus), ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus), spotted flycatcher (Muscicapa striata), wood warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava), yellowhammer (Emberiza citronella)

People

Wildlife watching, berry picking, foraging, camping and glamping, cycling, fruit growing, regenerative farming, stalking, walking

These beautiful illustrations were created by Jeroen Helmer.

Demand a wilder future for our land

Send a message to the UK Government – it’s time to put nature in the frame. It only takes two minutes.

Add your name

Our vision

We have big ambitions. Find out what we’ve set out to achieve through rewilding.

Our vision